Puggle Publishing House Co.

Dorothy Ashton (Assistant Editor, 1931-1942)

Furrow's Fixers series

Puggle Publishing House Co. was a Melbourne-based Australian publishing company that operated from 1887 to 1942. Founded by brothers Edmund and Charles Doherty, the company initially focused on educational materials before becoming known for its children's literature, particularly the annual anthology Cracking Larks (1928-1940) and the controversial Furrow's Fixers mystery series (1934-1939).

The company's closure in 1942 was officially attributed to wartime economic pressures, though it had been severely damaged by the 1939 scandal surrounding the final Furrow's Fixers book, The Big Old Bush House, which was deemed inappropriate for children and led to widespread controversy.

- 1 History

- 1.1 Colonial Beginnings (1887-1914)

- 1.2 The Wickham Era (1914-1934)

- 2 The Furrow's Fixers Phenomenon

- 2.1 The Mysterious R.D. Rowland

- 2.2 Series Success (1934-1938)

- 3 The 1939 Scandal

- 3.1 Arrival of "The Big Old Bush House"

- 3.2 Scandal and Aftermath

- 3.3 The Mystery Deepens

- 4 Decline and Closure (1940-1942)

- 5 Legacy and Subsequent Research

- 5.1 The Whyburn House Connection

- 5.2 Theories and Speculation

- 6 Cultural Influence

- 7 References and Archives

History

Colonial Beginnings (1887-1914)

Puggle Publishing House Co. was established in Melbourne in 1887 by brothers Edmund and Charles Doherty, former compositors at The Argus newspaper who had harboured dreams of literary independence. The company name, taken from the colloquial term for a young echidna, was meant to evoke something distinctly Australian—though critics at the time found it rather undignified for a firm with serious aspirations.

The Doherty brothers initially focused on what Edmund termed "instructional literature for the improvement of colonial youth" which historians have deemed a rather grandiose description for cheaply produced pamphlets on topics ranging from basic arithmetic to moral comportment. These early publications were largely forgettable, though their 1889 volume "The Young Australian's Guide to Proper Penmanship" did enjoy modest success in Victorian classrooms.

The company's fortunes changed dramatically in 1893 when they secured the Australian rights to publish several popular British story papers. This arrangement proved lucrative enough to allow the Doherty brothers to move from their cramped offices above a tobacconist's shop on Bourke Street to more respectable premises on Collins Street. By the turn of the century, Puggle Publishing had established itself as a reliable, if unexceptional, presence in Australian publishing. At this point they were known primarily for school primers, agricultural guides, and the occasional novel of questionable literary merit.

Charles Doherty died in 1902 following a riding accident, leaving Edmund as sole proprietor. Edmund proved less interested in day-to-day operations than his brother had been, preferring to spend his time at the Melbourne Club discussing literature rather than producing it. He hired a young man named Herbert Wickham as managing editor in 1905, a decision that would ultimately reshape the company's trajectory.

The Wickham Era and the Birth of Cracking Larks (1914-1934)

Herbert Wickham was a peculiar fellow: short, bespectacled and possessed of an encyclopaedic knowledge of children's literature from around the world. Where Edmund Doherty saw publishing as a gentleman's vocation, Wickham saw it as both art and industry. He had grown up reading penny dreadfuls and serialised adventures, and he believed passionately that Australian children deserved their own homegrown stories rather than endless imports from Britain and America.

When the Great War began in 1914, Wickham found himself in charge of Puggle Publishing's operations, as Edmund had volunteered for service despite being well past the usual age (he served as an officer and never saw combat). Wickham used this opportunity to begin experimenting with original Australian content. His first venture was a series of pamphlets featuring bush legends and Aboriginal stories, respectfully adapted with consultation from Indigenous Elders. This was a progressive approach for the era, though one that sold poorly.

Undeterred, Wickham persevered. In 1920, he launched "The Young Australian's Story Paper," a monthly periodical featuring adventure stories, nature articles, and puzzles. It achieved moderate circulation, primarily in Victoria and New South Wales. More significantly, it established Puggle Publishing as a company interested in local talent.

Edmund Doherty returned from the war in 1919 and was bewildered by the changes Wickham had implemented, and promptly retired to his country property near Geelong, leaving Wickham complete creative control. Edmund died in 1926, and his will revealed that he had, somewhat carelessly, never updated his business succession plans. The company passed to a distant cousin in Adelaide who had no interest in publishing and was happy to let Wickham continue running things in exchange for a share of profits.

The true masterstroke came in 1928 when Wickham conceived of an annual anthology aimed at young readers aged eight to fourteen. He wanted something that felt like an event, a book that children would anticipate each year, that parents would purchase as a reliable Christmas gift, that would become a fixture of Australian childhoods. After considerable deliberation (and several rejected titles including "The Young Australian's Annual" and "Bush Tales and Adventures"), he settled on Cracking Larks—a name that captured the energetic, optimistic spirit he hoped to convey.

The first edition of Cracking Larks, published in November 1928, was a handsome volume bound in deep green cloth. It contained a mixture of adventure stories, natural history articles, puzzles, and illustrations by some of Melbourne's better commercial artists. Wickham had solicited contributions from established Australian authors as well as promising newcomers, and he'd insisted on paying rates comparable to what British publications offered. This approach earned him loyalty from his numerous contributors.

Cracking Larks 1928 sold respectably but not spectacularly, enough to justify a second edition. The 1929 edition did better still. By 1931, Cracking Larks had become a minor institution, with children writing letters to Puggle Publishing House throughout the year suggesting story ideas and asking when the next volume would appear.

The anthology's success allowed Wickham to expand Puggle's operations. He hired additional staff, including a sharp young woman named Dorothy Ashton as assistant editor in 1931. This move was scandalous in some circles, though Wickham defended the appointment by noting that women were the primary purchasers of children's books and might therefore have valuable insights into what sold. He also began publishing standalone novels by authors who had first appeared in Cracking Larks, creating something of a literary proving ground for future projects.

The Furrow's Fixers Phenomenon

The Mysterious R.D. Rowland

The 1934 edition of Cracking Larks was in production during the winter months of that year, with Wickham and Ashton reviewing submissions in their Collins Street offices. The anthology had become a well-oiled machine by this point, with regular contributors and a reliable stable of artists. Most submissions arrived through the post in the conventional manner, occasionally delivered by hand by Melbourne-based writers.

It was therefore somewhat unusual when, on a grey morning in June 1934, a manuscript arrived in a blue envelope with no return address. The postmark indicated it had been sent from somewhere in New South Wales, though the exact location was smudged and illegible. Inside was a handwritten story titled "Furrow's Fixers and the Case of the Missing Cake," authored by one R.D. Rowland.

Dorothy Ashton later recalled in a 1967 interview for the oral history project "Crackers and Corkers: Publishing Memories from the Puggle Years" that the handwriting itself was remarkable "almost calligraphic in its precision, yet, I'm not sure how to say it but urgent, as though written in great haste by someone trained in excellent penmanship." The manuscript was accompanied by no cover letter, no biographical note, no contact information beyond a single line at the bottom of the final page: "Further correspondence may be directed to R.D. Rowland, care of Puggle Publishing House." but no address was listed here either. The note, Ashton thought, was rather presumptuous.

The story itself was charming: a light mystery involving twin children, Constance and Christian Marsh, who lived on a property called Ploughman's Furrow near a fictional bush town called Wentworth. The twins were nine years old in the story, and the case they solved (the theft of their mother's cake from a CWA bake sale by a jealous rival named Mrs. Abernathy) was delightfully small-scale yet treated with the gravity of a major crime. The writing had an authentic voice. It was distinctly Australian in setting and vernacular, yet with echoes of the popular British adventure stories that dominated children's reading.

Wickham was immediately taken with it. He'd been hoping to include more serialisable characters in Cracking Larks—the anthology format made it difficult to build reader loyalty to recurring personalities. Here was a perfect opportunity: child detectives in a recognisable Australian setting, solving problems that felt real to young readers. He accepted the story for Cracking Larks 1934 and sent a letter to "R.D. Rowland, care of Puggle Publishing House" expressing his enthusiasm and inquiring whether the author might be interested in submitting additional stories.

The letter was filed in Puggle's incoming correspondence, where it remained unclaimed. No R.D. Rowland ever appeared to collect it.

Series Success (1934-1938)

Cracking Larks 1934 was published in November of that year and sold better than any previous edition. While it would be an exaggeration to credit the Fixers story entirely for this success readers' letters made clear that Constance and Christian Marsh had struck a chord. Children wrote asking for more Fixers stories. Parents mentioned the characters favourably in letters praising the anthology. One reviewer in The Sydney Morning Herald specifically singled out "the delightful Marsh twins" as exemplifying the kind of Australian characters young readers deserved to see more of.

Wickham immediately wrote to R.D. Rowland (again, care of the publishing house) expressing hope that more Fixers stories might be forthcoming and suggesting that a series of standalone books might be commercially viable. This letter, like the first, went unclaimed.

Then, in December 1934, another blue envelope arrived.

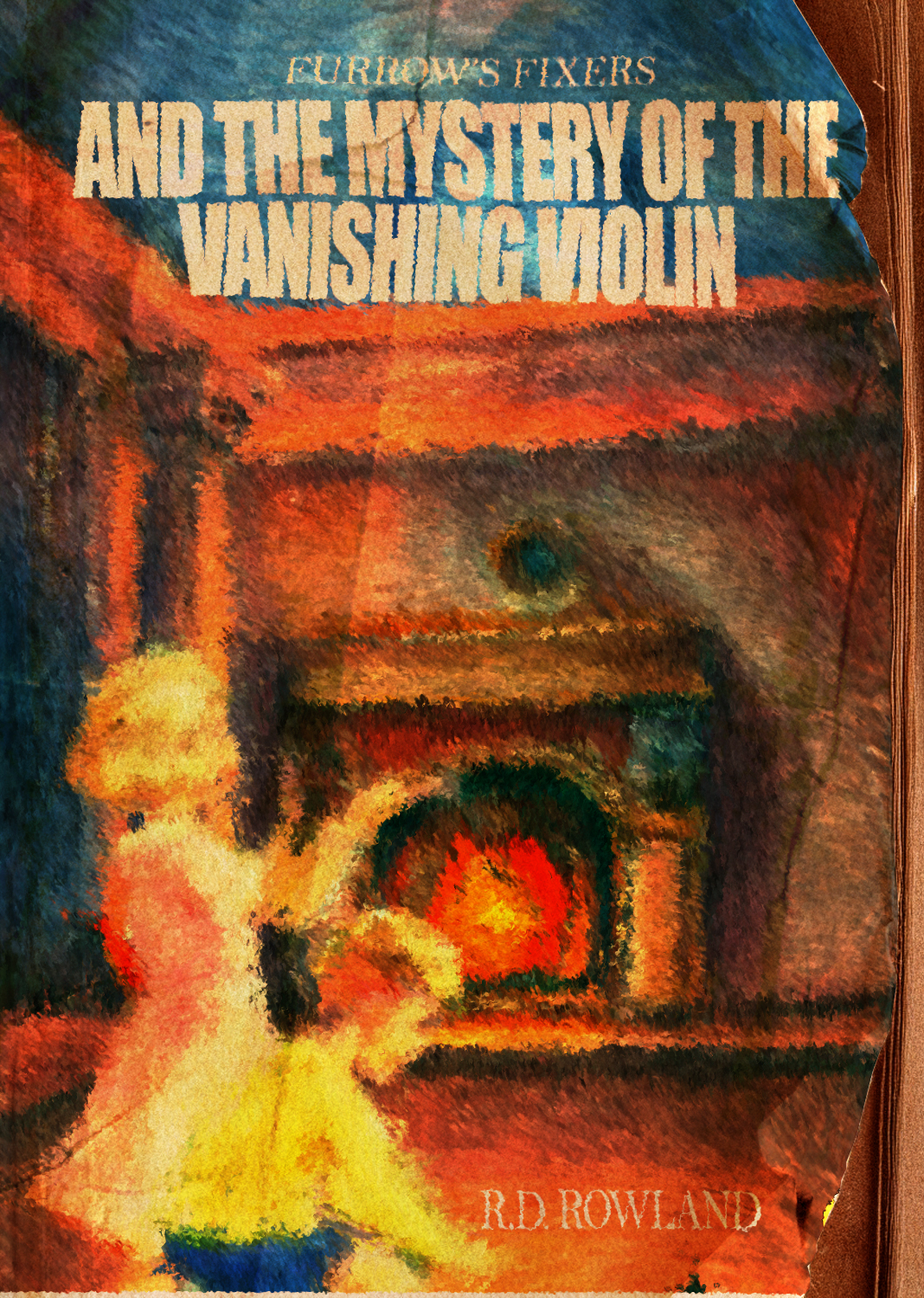

Inside was a complete manuscript for a novel titled "Furrow's Fixers and the Mystery of the Vanishing Violin." It was considerably longer than the Cracking Larks story at approximately 35,000 words. This novel featured the Marsh twins, now aged eleven, investigating the theft of a valuable instrument from their music teacher during the Christmas holidays. The story was expertly plotted, with genuine clues, red herrings, and a satisfying resolution. Once again, there was no cover letter, no biographical information, just the byline R.D. Rowland and that single line directing correspondence to Puggle Publishing House.

Wickham discussed the manuscript with Dorothy Ashton. Both agreed it was publication-worthy, but both were also troubled by the author's anonymity. According to their later accounts in "Crackers and Corkers," Ashton suggested rejecting it on principle, to which Wickham responded, "We could... But it would be a damned shame. It's good, Dorothy. Really quite good." After considerable deliberation, they decided to proceed with publication despite the irregularity.

They prepared a contract offering standard terms and addressed it to "R.D. Rowland, care of Puggle Publishing House." In a baffling turn, the signed contract arrived three weeks later in another blue envelope, with bank details for an account at the Bank of New South Wales in Bathurst—concrete evidence that R.D. Rowland was a real person, yet one who remained determinedly anonymous.

"Furrow's Fixers and the Mystery of the Vanishing Violin" was published in April 1935. Puggle Publishing marketed it modestly, as they were still primarily known for Cracking Larks and their educational books. The book sold steadily if not spectacularly through autumn and winter. Interestingly, the story made reference to bore baths in the fictional town of Wentworth, a detail that would later prove significant to researchers investigating the series' geographical basis.

Then, in June 1935, another blue envelope arrived containing "Furrow's Fixers and the Secret of the Scribbly Gum."

A pattern was establishing itself: two manuscripts per year, arriving like clockwork in June and December, each in an identical blue envelope, each featuring the Marsh twins solving mysteries during their school holidays. Wickham attempted numerous times to establish contact with R.D. Rowland through letters sent to the bank in Bathurst (which were returned as undeliverable), through notices placed in regional New South Wales newspapers (which went unanswered), and even through a half-hearted attempt to have Dorothy Ashton travel to Bathurst to investigate (which she sensibly declined, pointing out that hunting down a pseudonymous author who clearly valued privacy was both impractical and possibly unethical).

Wickham eventually accepted the situation's peculiarity and focused on the commercial opportunity. Each Fixers book was released six months apart, April and December, timed to coincide with Easter and Christmas holidays, just like the stories themselves. This proved brilliantly effective marketing. Children who'd read about the Marsh twins' Christmas adventures could immediately experience their Easter adventures, creating a sense of real-time continuity.

The books' popularity grew steadily. By 1936, the Fixers series was Puggle Publishing's bestselling line. Constance and Christian Marsh appeared on the covers of Cracking Larks editions. Fan letters arrived addressed to the Marsh twins care of Puggle Publishing House. Schools incorporated the books into their libraries. Parents discovered they made reliable gifts.

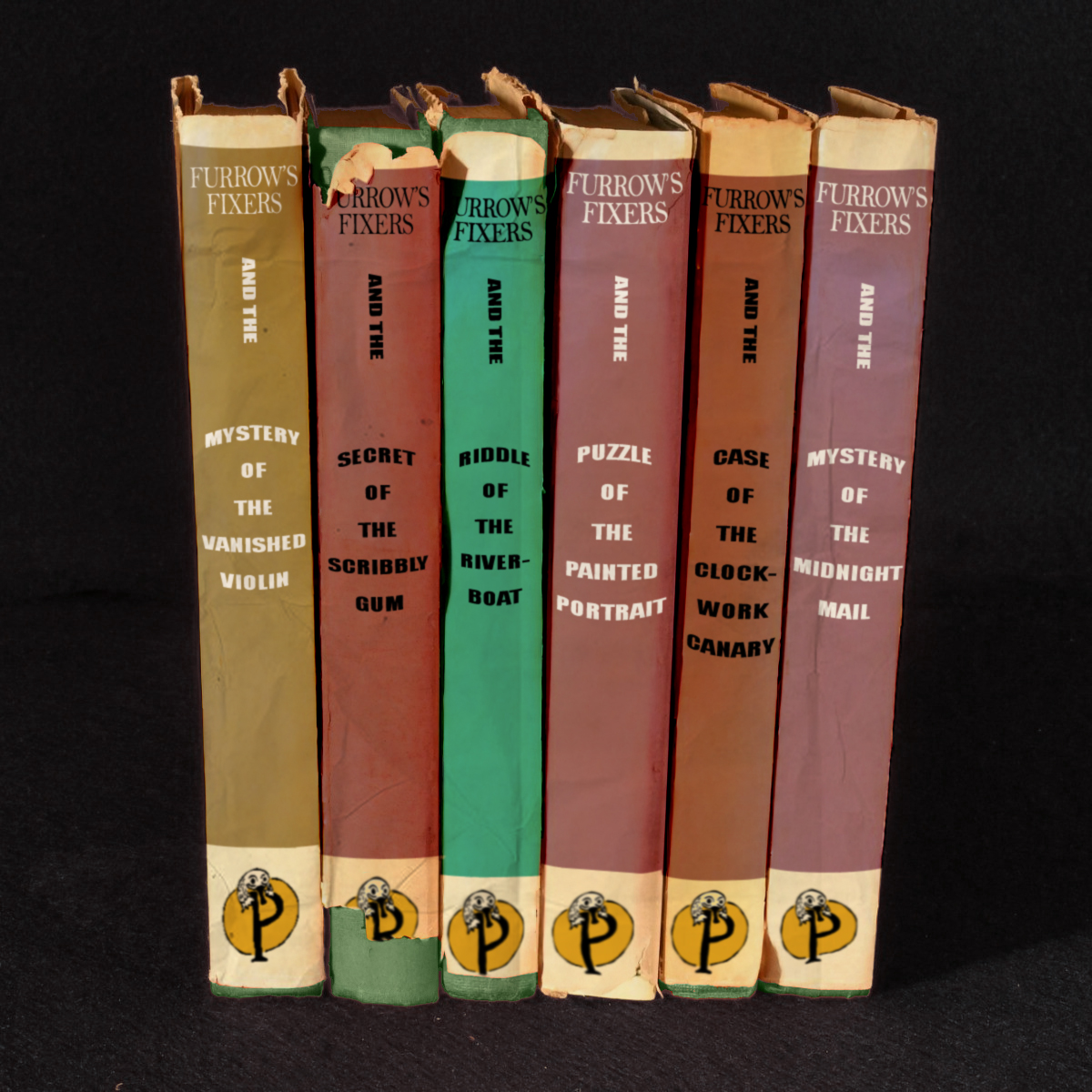

The titles during this period included:

- "Furrow's Fixers and the Mystery of the Vanishing Violin" (April 1935)

- "Furrow's Fixers and the Secret of the Scribbly Gum" (December 1935)

- "Furrow's Fixers and the Riddle of the Riverboat" (April 1936)

- "Furrow's Fixers and the Puzzle of the Painted Portrait" (December 1936)

- "Furrow's Fixers and the Case of the Clockwork Canary" (April 1937)

- "Furrow's Fixers and the Mystery of the Midnight Mail" (December 1937)

- "Furrow's Fixers and the Adventure of the Ancient Map" (April 1938)

- "Furrow's Fixers and the Enigma of the Empty Estate" (December 1938)

- "Furrow's Fixers and the Treasure of the Mysterious Rover" (April 1939)

Each story maintained the series' winning formula: the Marsh twins returning from their respective boarding schools, catching up on local news, engaging in their characteristic "troving" (researching at libraries, museums, and archives), and ultimately solving mysteries that ranged from the whimsical to the genuinely intriguing. The books were wholesome without being preachy, Australian without being self-consciously nationalistic, and clever without being condescending.

R.D. Rowland's identity remained a mystery, albeit one that Puggle Publishing had learned to leverage. Advertisements for the books played up the enigmatic author: "Written by the mysterious R.D. Rowland! Who are they? Where are they? Only the Fixers might be able to solve that mystery!" It was good marketing, and it sold books.

Herbert Wickham, now in his fifties and increasingly content to let Dorothy Ashton handle much of the editorial work, had reason to be satisfied. Puggle Publishing was thriving. Cracking Larks remained popular. The Fixers series had established the company as a significant player in Australian children's literature. Everything was proceeding exactly according to plan.

Until December 1939.

The 1939 Scandal

Arrival of "The Big Old Bush House" (September 1939-December 1939)

The blue envelope that arrived in September 1939 seemed no different from the nine that had preceded it since the series' inception. It was the expected weight, the expected size, postmarked from somewhere in New South Wales (the postmark was, as always, conveniently illegible). Dorothy Ashton opened it at her desk on a warm afternoon, expecting another wholesome mystery adventure.

What she found instead would haunt Puggle Publishing for years to come.

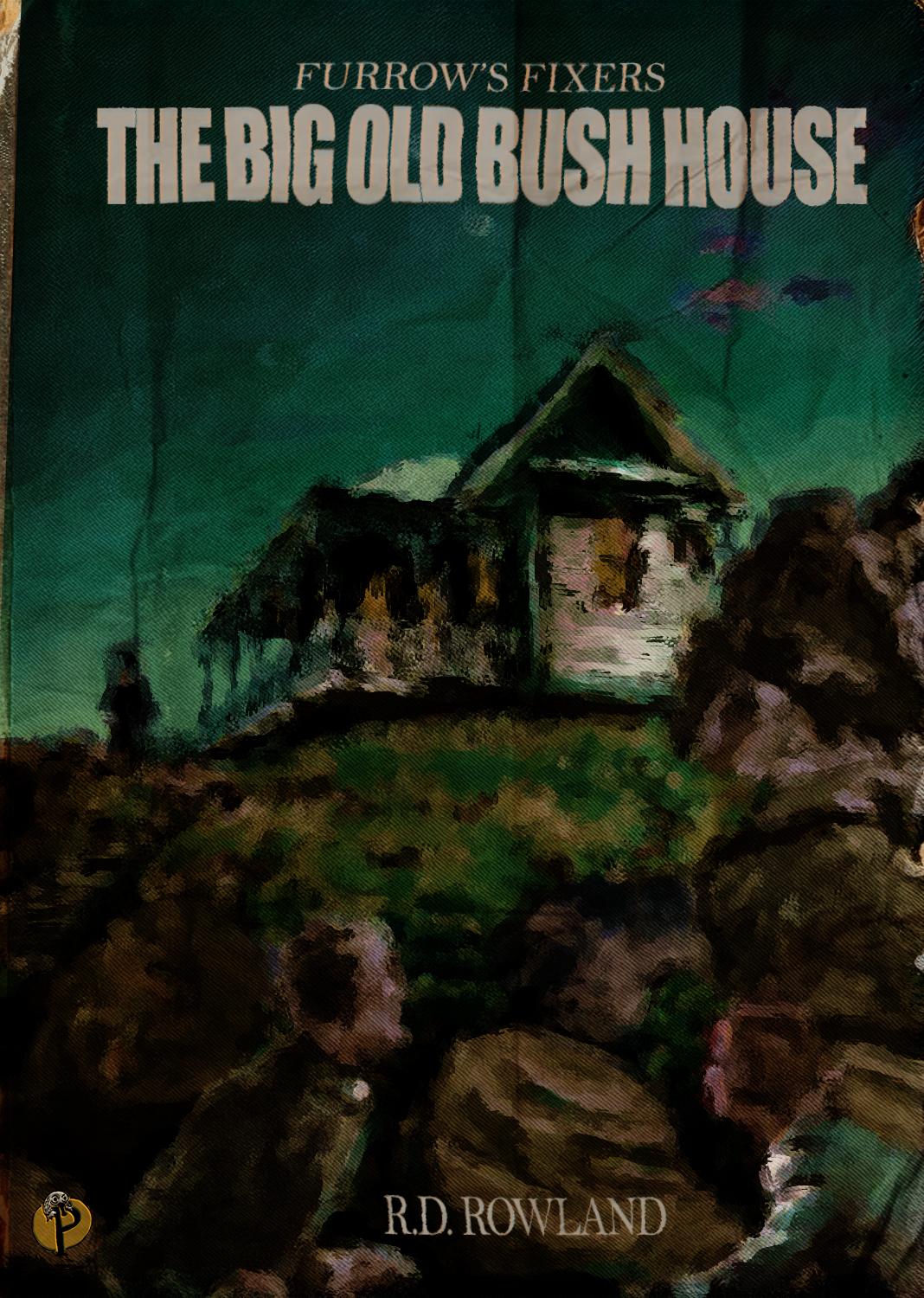

The manuscript was titled "Furrow's Fixers and the Big Old Bush House," and it began conventionally enough. The Marsh twins, now fourteen years old, returned to Ploughman's Furrow for the Christmas holidays. They heard about a mysterious newcomer to the area—a Mr. Thornton Grice who had moved into the long-abandoned Whyburn house on Settler's Ridge. They began investigating, troving at the library, uncovering clues about the house's former owner, Ephraim Whyburn, and his hidden collection of antiquities.

So far, entirely in keeping with the series' established pattern.

But approximately one-third of the way through the manuscript, something shifted. The tone darkened. The story that had seemed like a straightforward mystery about treasure hunting began to veer into territory that Dorothy Ashton found increasingly disturbing. By the time she reached the final page, she felt physically ill.

She immediately took the manuscript to Herbert Wickham. Wickham read it that evening and returned to the office the next morning looking haggard. According to their accounts in "Crackers and Corkers," Wickham stated simply, "We can't publish this," to which Ashton agreed emphatically. The oral history records that both editors were deeply shaken by the manuscript's content and spent considerable time debating what action to take.

The question was what to do. R.D. Rowland had never failed to deliver a manuscript on schedule. Readers were expecting the next Fixers adventure in December 1939. Contracts with booksellers had been signed. Advertisements had been placed. Children across Australia were anticipating the Marsh twins' next adventure.

Wickham composed a letter, the most carefully worded letter of his career, explaining that the submitted manuscript was unsuitable for publication and requesting that R.D. Rowland submit a replacement. He detailed the specific objections (in language sufficiently vague that the letter itself wouldn't be inappropriate should anyone else read it) and emphasised that Puggle Publishing had always valued their relationship with R.D. Rowland and hoped it would continue with material more in keeping with the series' established character.

This letter was sent to the Bank of New South Wales in Bathurst, to the "care of Puggle Publishing House" address (despite knowing it would go unclaimed), and even, in a fit of desperation, as a notice in the classified sections of newspapers throughout regional New South Wales: "R.D. Rowland: Please contact Puggle Publishing regarding recent submission. Urgent."

No response came.

October 1939 passed. November arrived. Wickham and Ashton faced an impossible situation. They had no manuscript, no way to contact their author, and an increasingly anxious network of booksellers and distributors asking about the December publication. As documented in Ashton's personal papers, she suggested various alternatives including commissioning a ghostwriter or reissuing an earlier book, all of which Wickham rejected as either fraudulent or commercially unviable.

Then, in mid-November, a letter arrived. It was not in the usual blue envelope. It was in a plain manila envelope, postmarked from Sydney, written in a different hand—scratchy and hurried rather than elegantly calligraphed. It was addressed to Herbert Wickham personally.

The letter was unsigned, but its content was unambiguous:

According to "Crackers and Corkers," Wickham and Ashton stared at this letter in stunned silence before Ashton identified it as coming from R.D. Rowland, telling them "to either publish that... that thing... or publish nothing at all." The oral history records several days of agonised deliberation, with Wickham developing what Ashton described as "a peculiar obsession with the question of why" an author would deliberately sabotage a successful series.

After considerable internal debate involving printers, lawyers, and accountants, Wickham made his controversial decision. Puggle Publishing would release "Furrow's Fixers and the Big Old Bush House" exactly as submitted, with only minimal copyediting, but in a limited run of just 2,000 copies with no advertising campaign. Dorothy Ashton argued strenuously against this plan and was overruled—an experience she would later note bitterly was "one of the inevitable experiences of being a woman in publishing."

"Furrow's Fixers and the Big Old Bush House" was published in December 1939 (though as a side note the book's cover just read 'Furrow's Fixers The Big Old Bush House' leaving the and off, the and is present on the spine of the book and as it matches the naming pattern of the rest of the series "Furrow's Fixers and the Big Old Bush House" is considered the official title).

Scandal and Aftermath (December 1939-June 1940)

The first hint that something was wrong came within days of publication. A bookseller in Newcastle telephoned Puggle Publishing in a state of high agitation, demanding to know if the company had actually read the book they'd published. Similar calls followed from Sydney, from Canberra, from Adelaide.

Then the letters began arriving. From outraged parents. From school librarians demanding refunds. From religious organisations threatening boycotts. The accusations varied in specifics but shared common themes: the book was obscene, it promoted occultism, it was psychologically damaging to children, it was evidence of moral decay in Australian publishing.

Wickham requested that a staff member provide a summary of the specific objections, since the complaints were becoming too numerous to read individually. The summary made for grim reading:

The manuscript began as a conventional mystery, but approximately one-third through, the story took a dark turn. The "hidden collection" that the Marsh twins were investigating turned out to involve not merely antiquities but artefacts of a decidedly occult nature. The mysterious Mr. Grice was revealed to be not a simple treasure hunter but a practitioner of pagan magicks. The narrative included descriptions of ceremonies that several clergy members labelled as satanic. There were implications of sacrifice. Of corruption. Of ancient evils awakened.

More troubling still were the scenes involving Constance and Christian themselves. The twins, whom readers had followed since age nine, were now depicted in situations of genuine peril and not the cosy, easily-resolved dangers of previous books. These were real psychological and physical threats. There were passages that implied violence with a vividness entirely inappropriate for the series' target audience especially for the time it was produced. And there was a scene, described by one reviewer as "grotesquely unsuitable", in which Christian discovered something in the Whyburn house's hidden vault that left him temporarily mute with horror, the description of which was visceral enough that several readers reported nightmares.

But perhaps most disturbing was the book's ending. Previous Fixers adventures had concluded with mysteries solved, order restored, and the Marsh twins safely back at Ploughman's Furrow awaiting their next adventure. "The Big Old Bush House" ended ambiguously, with suggestions that not everything had been resolved, that dangers remained, and that the twins themselves had been fundamentally changed by their experience.

This was the holiday where the Furrow's Fixers found out that some things cannot be fixed."

For readers accustomed to tidy resolutions and cheerful endings, this was profoundly unsettling.

The controversy exploded. The Sydney Morning Herald ran an editorial titled "What Has Happened to Australian Children's Literature?" The Melbourne Age published a lengthy article investigating "the mysterious R.D. Rowland and the scandalous Fixers finale." Conservative groups called for the book to be banned. Progressive groups defended it as an example of artistic freedom, though many admitted they hadn't actually read it and were arguing from principle rather than content.

Several particularly enterprising journalists attempted to track down R.D. Rowland, but their investigations led nowhere. The bank account in Bathurst existed but was held under a trust arrangement that protected the account holder's identity. The postmarks on the blue envelopes were examined but provided no useful information. No one named R.D. Rowland (or any plausible variation) could be found in regional New South Wales who had any connection to children's literature.

Rumours proliferated. R.D. Rowland was a collective pseudonym for multiple authors. R.D. Rowland was a disgraced academic working out personal demons through fiction. R.D. Rowland was a woman who'd hidden her gender behind initials and was now making a feminist statement about the darkness underlying children's adventure stories. R.D. Rowland had never existed and the manuscripts were found documents, perhaps genuine diaries that Puggle Publishing had fictionalised. R.D. Rowland was someone at Puggle Publishing itself, perpetrating an elaborate hoax.

Herbert Wickham refused all interview requests. Dorothy Ashton, who had opposed publication, found herself in the awkward position of defending her employer's decision while privately maintaining she'd been right to oppose it. The remaining staff at Puggle Publishing kept their heads down and hoped the storm would pass.

It did not pass.

Booksellers returned unsold copies by the hundreds. Libraries quietly removed the book from shelves. Parents who'd purchased copies wrote demanding refunds. A few copies were publicly burned at a rally organised by a religious group in Sydney. An event that made front-page news and only intensified the controversy.

But here was the strange thing: amid all the outrage, there were readers (mostly older children and young adults) who defended the book. Letters arrived at Puggle Publishing praising "The Big Old Bush House" as a mature, sophisticated work that took young readers seriously. Several reviewers, writing in more literary-minded publications, suggested that R.D. Rowland had deliberately subverted the adventure genre to make a point about the darkness underlying Australia's colonial history and the dangers of excavating the past without understanding its context.

"The book," wrote one particularly perceptive critic in Meanjin Quarterly, "is not inappropriate for children because it is obscene. It is inappropriate because it tells truths about the world that we prefer children not yet understand. That is not the book's failure. It is ours."

Perhaps most provocatively, a prominent South Australian literary critic, Professor Edmund Hartley, writing in The Adelaide Review, proposed that the book functioned as "a cipher rather than a conventional narrative—a text so deliberately overdetermined with possible meanings that it resists singular interpretation. There are too many readings available, too many symbols in play, for any one analysis to be definitive. Perhaps Rowland's intention was not to communicate a specific message but to create a Rorschach test for an infant nation still grappling with its superiority complex and colonial anxieties. What we see in 'The Big Old Bush House' may reveal more about ourselves than about the author's intent."

This more nuanced defence made little difference commercially. "Furrow's Fixers and the Big Old Bush House" was a catastrophic failure from a business perspective. Puggle Publishing lost money on the print run and suffered significant reputational damage. Several booksellers severed relationships with the company. Distribution channels that had carried Cracking Larks for years declined to carry future editions.

Most devastating of all: the Fixers series was finished. Even if R.D. Rowland submitted a new manuscript (which seemed unlikely) no bookseller would carry it. The brand was poisoned.

Wickham, who had believed he was making a principled decision about authorial integrity, found himself condemned from all sides. Those who opposed the book's publication blamed him for allowing it to be released. Those who defended it as art blamed him for not supporting it more forcefully. He could satisfy no one, including himself.

The Mystery Deepens (July 1940)

In July 1940, as the controversy was finally beginning to fade from public consciousness, another blue envelope arrived at Puggle Publishing House.

Dorothy Ashton opened it with a sense of profound dread.

Inside was a brief handwritten note:

R.D. Rowland"

There was no manuscript. Just this cryptic farewell.

As Ashton later recalled in a 1971 letter to Dr. Margaret Sutherland, she showed the note to Wickham and they sat in silence for a long moment. "Do you think they're real?" she asked finally. "The twins. Do you think Constance and Christian Marsh actually existed?" Though Wickham dismissed the suggestion, Ashton noted that "his voice lacked conviction." She continued to wonder whether R.D. Rowland had been "writing from life" and whether they had been "publishing someone's testimony disguised as children's fiction."

Wickham placed the note in a file marked "R.D. Rowland Correspondence"—a file that contained mostly returned letters and unanswered queries.

No further communication ever arrived from R.D. Rowland.

Decline and Closure (1940-1942)

The scandal surrounding "The Big Old Bush House" damaged Puggle Publishing irreparably. The 1939 edition of Cracking Larks sold poorly. The 1940 edition sold even worse. Booksellers who'd once prominently displayed Puggle's books now relegated them to back shelves or declined to stock them entirely.

The war didn't help. As Australia mobilised, paper became scarce, distribution networks were disrupted, and public attention focused on matters more pressing than children's literature. Several of Puggle's staff enlisted or took positions in war-related industries. Herbert Wickham, now in his sixties and exhausted by the Fixers debacle, seriously considered retirement.

In 1941, Puggle Publishing released only three books, a far cry from their productive years in the mid-1930s. Cracking Larks was discontinued after the 1940 edition, ending a tradition that had lasted twelve years.

Dorothy Ashton left in early 1942 to take a position with Angus & Robertson, one of Puggle's larger competitors. In her farewell letter to Wickham, she wrote:

Wickham closed Puggle Publishing House in August 1942. The official reason given was "wartime economic pressures," which was true enough. The unofficial reason was that Wickham had lost his enthusiasm for the business, haunted by questions he couldn't answer and decisions he couldn't unmake.

The company's backlist was sold to various publishers. Its archives (including all correspondence, contracts, and manuscripts) were donated to the State Library of Victoria, where they remain available to researchers, though few have examined them in detail. The original manuscripts in R.D. Rowland's distinctive handwriting are stored in climate-controlled conditions, pristine and inexplicable.

Herbert Wickham retired to Brighton and died in 1951, never having given a public interview about the Fixers scandal. In his personal papers, donated to the State Library after his death, there is a single notation in a diary entry from December 1939:

Legacy and Subsequent Research

In the decades since Puggle Publishing's closure, the Furrow's Fixers series has become a footnote in Australian literary history. It is remembered, if at all, primarily for its scandalous conclusion rather than its four years of wholesome success. The first nine books occasionally appear in antiquarian bookshops, modestly priced and rarely purchased. "The Big Old Bush House," by contrast, has become a collector's item, with surviving copies fetching substantial sums from collectors of curiosa and literary scandal. Strangely, though the book has never been officially reprinted, it remains the most sought-after volume in the series.

Several researchers have attempted to identify R.D. Rowland, without success. The most thorough investigation, conducted by Dr. Margaret Sutherland for her 1978 doctoral thesis "Pseudonymity and Authorship in Australian Children's Literature," concluded that R.D. Rowland was likely a single individual rather than a collective pseudonym, probably female (based on handwriting analysis and certain stylistic elements), probably living in rural New South Wales, and probably someone with either personal experience of the region described in the books or access to detailed information about it.

But beyond these tentative conclusions, R.D. Rowland's identity remains unknown.

There is, however, one curious footnote to Dr. Sutherland's research. While investigating property records in regional New South Wales, she discovered that a property named "Ploughman's Furrow" had indeed existed near the town of Bourke not the fictional "Wentworth" of the books, but a real town in the northwest of the state. The property was registered to a family named Marsh.

Dr. Sutherland attempted to trace the Marsh family's history but encountered frustrating dead ends. Records showed that the property was sold in 1939 (the same year "The Big Old Bush House" was published) to a distant relative who subsequently subdivided and sold the land. The original homestead was demolished in 1947. Electoral rolls and census records confirmed that a family named Marsh had lived at the property during the 1920s and 1930s, and that this family had included at least two children, but beyond these basic facts, information was scarce.

Most intriguingly, Dr. Sutherland discovered that the local cemetery had contained two graves side by side, dated 1938, belonging to individuals identified only by their given names: Constance and Christian. The surnames on the headstones had weathered to illegibility, and cemetery records from that period had been lost in a fire in 1952.

Dr. Sutherland included this information as an appendix to her thesis but cautioned against drawing definitive conclusions. "The coincidence of names and location is striking," she wrote, "but coincidences do occur. Without additional evidence, we cannot determine whether R.D. Rowland was writing fiction inspired by real people and places, or whether the parallels are simply artefacts of research and imagination."

She did, however, note one detail that she found "disquieting": the dates on the cemetery headstones indicated that Constance and Christian had died in December 1938, approximately twelve months before "Furrow's Fixers and the Big Old Bush House" was published.

The Whyburn House Connection

There is one final element to this story that deserves mention, though it strays from publishing history into something more speculative and historically significant.

In 1976, a journalist named Peter Galloway wrote an article for The Australian titled "The Real Big Old Bush House?" In it, he described travelling to the Bourke district in New South Wales and investigating the historical connections between R.D. Rowland's fictional "Wentworth" and the real town of Bourke.

What Galloway discovered was both fascinating and unsettling.

The fictional town in the Fixers series was called "Wentworth" a name that appeared repeatedly throughout the books as the setting for the Marsh twins' adventures. This seemed like a simple authorial choice, perhaps inspired by the well-known Wentworth family of Australian colonial history, or by one of the several towns named Wentworth across Australia.

But Galloway's research revealed something more intriguing: near Bourke, there stood (and still stands) a grand old house known locally as Martindale House, built in the late nineteenth century. This house had been owned throughout its history by members of the Wentworth family specifically, distant relatives of the descendants of William Charles Wentworth, the explorer and statesman who had been instrumental in the attempts to establish an Australian aristocracy in the colonial period.

Martindale House itself is remarkable: a substantial two-storey building in the Colonial style, considerably more elaborate than most bush homesteads of its era, suggesting the wealth and social aspirations of its owners. Over the decades, the property expanded, with additional buildings constructed around the original house in a more utilitarian, modern style. By the 1970s, when Galloway visited, Martindale House formed the centrepiece of what had become a larger compound, with the grand old residence looking somewhat incongruous amongst its newer, hastier neighbours.

The house's association with the Wentworth family and through them, with Australia's brief flirtation with establishing a colonial aristocracy gave it a peculiar historical weight. The Wentworths had been amongst those who advocated for hereditary titles and formal class structures in the Australian colonies, proposals that were ultimately rejected in favour of more egalitarian principles. The family's mansions and estates scattered across New South Wales stood as monuments to this failed aristocratic dream.

What made this relevant to the Fixers mystery was the uncanny parallel: in R.D. Rowland's final book, the mysterious and sinister "Whyburn house" sat on Wentworth's Ridge overlooking the fictional town of Wentworth. In reality, a grand house (Martindale House) existed near Bourke, owned by a family named Wentworth.

The reversal seemed deliberate as if R.D. Rowland was making some kind of statement about the relationship between names, places, and power. Was the fictional "Wentworth" a stand-in for Bourke? And if so, what was R.D. Rowland saying by naming the town after the family that owned the real house?

Galloway noted several other correspondences between R.D. Rowland's fictional Wentworth and the real Bourke:

- The books mention "Richard Street" as a main thoroughfare in Wentworth. Bourke has a Richard Street, where the town's war memorial stands matching a description in one of the early Fixers books.

- The fictional Wentworth has a post office that features prominently in several stories, described with specific architectural details including "fruit trees in the front courtyard." Bourke's post office, a handsome building from the Federation period, matches this description almost exactly.

- The bore baths mentioned in "The Mystery of the Vanishing Violin" correspond to Bourke's actual bore baths, a distinctive local feature.

Several minor characters in the books: shopkeepers, clergymen, town officials and more all have names that appear in Bourke's historical records from the 1930s, though whether these are deliberate references or coincidences is impossible to determine.

Most tellingly, the description of the Whyburn house in R.D. Rowland's final book closely matches Martindale House: a two-storey Colonial structure with wide verandas and elaborate iron lacework, sitting on elevated ground overlooking the surrounding countryside.

Galloway interviewed several elderly residents of the Bourke area who remembered the 1930s. One woman, identified only as "Mrs. E.," claimed to recall a family named Marsh who had lived on a property near Bourke during that period.

"There were two children," Mrs. E. told Galloway. "Twins, I believe. Brother and sister. They went away to school, came back for holidays. Studious types, always at the library, always asking questions about local history. The girl was particularly clever she had a mind like a steel trap."

When asked what happened to the family, Mrs. E.'s account became vaguer. She mentioned "something tragic" in late 1938, around Christmas time. "There was an accident of some kind. Both children went missing. The family left soon after [...]couldn't bear to stay, I suppose. It was all very hushed up. Some things people don't like to talk about."

Galloway also discovered that in the late 1930s, Martindale House had been leased to a Melbourne gentleman with interests in antiquities and Eastern mysticism. This gentleman arrived in 1938 and departed rather suddenly in early 1939. Local records show he paid his lease through the end of the year despite leaving early, and that there was some kind of incident at the property in December 1938 that required police attendance, though the nature of the incident was not recorded in available documents.

Galloway's article concluded with a provocative suggestion: that R.D. Rowland's stories were not entirely fiction, but rather a disguised account of real events, with names and details altered just enough to provide plausible deniability. The fictional town of "Wentworth" was Bourke. The Whyburn house was Martindale House. And Constance and Christian Marsh were real children who died investigating something connected to that house and the powerful family who owned it.

"If this is true," Galloway wrote, "then 'Furrow's Fixers and the Big Old Bush House' was not a children's adventure gone wrong, but a testimony—a record of something dark that happened in December 1938, published in the only way R.D. Rowland could manage: as a story that everyone dismissed as inappropriate fiction."

Reception and Criticism of Galloway's Theory

Galloway's article was widely dismissed as sensationalised journalism. Critics pointed out numerous problems with his thesis:

- No death certificates could be located for Constance and Christian Marsh matching the details he described

- "Mrs. E." was never identified and could not be located for follow-up interviews

- The parallels between fictional Wentworth and real Bourke could easily be explained by authorial research rather than personal experience

- The idea that a powerful family would "hush up" deaths of children was melodramatic speculation without evidence

- In fact, when the Bourke cemetery records were checked (those that survived the 1952 fire), no graves matching the description could be definitively confirmed as belonging to children named Constance and Christian Marsh

Several members of the Wentworth family wrote letters to The Australian expressing outrage at Galloway's insinuations and threatening legal action if he continued to suggest their ancestors were involved in any impropriety. As part of the same statement they distanced themselves from the Wentworths outside Bourke, suggesting that they were a distant branch of the family (if they were related at all). Galloway published a brief retraction clarifying that he had made no specific accusations against any individuals, and that his article was merely exploring historical curiosities and literary mysteries.

The controversy faded quickly. Galloway never published further research on the topic, and he died in 1981 while en route to the Brighter Obtainable Bureau in a car accident, his notes and research materials apparently lost.

However, Galloway's article did inspire some researchers to take a closer look at Martindale House and its history. What they found was interesting, if not conclusive:

The house had indeed been associated with occult interests in the 1930s. Property records and family papers suggest that a tenant during this period (a gentleman from Melbourne with interests in antiquities) had assembled some kind of collection at the house. Local oral histories describe him as eccentric and reclusive. He departed the property abruptly in early 1940, and family correspondence from the period suggests there was "unpleasantness" that required the Wentworth family's intervention, though specifics were never recorded.

The Wentworth family maintained ownership of Martindale House throughout this period and into the present day. The house is now part of a larger working property and is not open to the public. Requests by researchers to examine the house or any remaining family papers have been politely declined.

Theories and Speculation

Over the years, various theories have emerged about R.D. Rowland and the Fixers series:

The Testimony Theory: That R.D. Rowland was someone connected to the Marsh family (perhaps a parent, relative, or family friend) who felt compelled to tell the true story of what happened to Constance and Christian in December 1938. The first nine books were published to establish the characters and build an audience, so that when the final book appeared, people would pay attention. The "inappropriate" content was not a literary miscalculation but the point: the truth is disturbing, and should be disturbing. This theory has questionable merit as it implies the writer would have forethought of what would occur.

The Warning Theory: That R.D. Rowland was attempting to warn readers about something real, perhaps the dangers of meddling with occult materials, or the way powerful families can cover up tragedies, or the darkness lurking beneath Australia's colonial aristocratic pretensions. The popular Fixers series was merely the vehicle for delivering this warning to a wide audience.

The Composite Theory: That R.D. Rowland combined elements from multiple real events. Including the actual Marsh children, the real Martindale House and its eccentric tenant, local rumours about the Wentworth family, and his or her own experiences or anxieties.

The Coincidence Theory: That R.D. Rowland was simply an author who did thorough research, chose the name "Wentworth" because it sounded appropriately Australian and colonial, happened to set the story in a region similar to Bourke, and created characters whose names and ages happened to match real people. The parallels, according to this theory, are the result of Australia being a relatively small country with limited naming conventions and repeated place names, combined with confirmation bias by researchers looking for connections.

The Literary Subversion Theory: That R.D. Rowland was a sophisticated literary artist deliberately working in the genre of children's adventure fiction in order to subvert it from within. The first nine books were conventional by design, establishing reader trust and expectations, so that the tenth book could violate those expectations and force readers (and their parents) to confront uncomfortable truths about the world: that evil exists, that children are not always safe, that authority figures cannot always protect them, and that happy endings are not guaranteed. The scandal was the point. Professor Hartley's cipher theory fits within this framework: perhaps R.D. Rowland deliberately created a text so overdetermined with meanings that it becomes a mirror for the reader's own anxieties and assumptions.

The Supernatural Theory: Occasionally proposed but rarely taken seriously, this theory suggests that the manuscripts were genuinely supernatural in origin. Written by the spirits of deceased children, or channelled through a medium, or produced through some other paranormal means. Proponents point to the distinctive handwriting, the mysterious blue envelopes, the author's complete absence from public record, and the prophetic or testimonial quality of the final book. This theory is generally dismissed by serious researchers.

Cultural Influence and Contemporary Significance

Puggle Publishing House is largely forgotten today except by specialists in Australian publishing history and collectors of vintage children's books. The Doherty brothers' original vision of producing educational materials for colonial youth has been entirely superseded by subsequent generations of publishers.

Cracking Larks is remembered, if at all, as a minor predecessor to the more successful Australian children's annuals that emerged in the post-war period. Several of the authors who got their start in Cracking Larks went on to have respectable careers, though none achieved lasting fame.

The Furrow's Fixers series occupies a peculiar position in literary history. They are too successful to be entirely obscure, too scandalous to be respectable, too mysterious to be easily categorised. The first nine books are occasionally reprinted by small speciality publishers catering to nostalgia markets, though these editions rarely sell in significant numbers. They are sometimes studied as examples of pre-war Australian children's literature, notable for their distinctly Australian settings and characters at a time when most children's books were still set in Britain.

"Furrow's Fixers and the Big Old Bush House" has never been officially reprinted, though it has appeared in various unauthorised editions and can be found in digital form on websites dedicated to rare and controversial books. Yet it remains, paradoxically, the most sought-after volume in the series. Collectors, scholars, and curious readers all want to read the book that caused such scandal, that ended a publishing house, that may or may not contain coded testimony about real events. Its status as forbidden or lost knowledge only intensifies its appeal.

The book is sometimes taught in university courses on children's literature, Australian Gothic fiction, or the history of literary censorship, where it serves as a case study in authorial intent, reader expectations, and the boundaries of genre. It has also attracted attention from scholars of Australian colonial history, particularly those interested in the social and cultural legacy of attempts to establish an Australian aristocracy.

Some see R.D. Rowland's choice to name the fictional town "Wentworth" and to place a house called "Whyburn" at the centre of a dark mystery as a deliberate commentary on the relationship between colonial power, land ownership, and secrets buried in Australia's past.

The name "Wentworth" carries significant weight in Australian history. William Charles Wentworth was not only an explorer but a politician and advocate who, paradoxically, fought both for Australian self-governance and for the establishment of a hereditary peerage system. The Wentworth family owned substantial properties across New South Wales, including Martindale House near Bourke. To anyone familiar with this history, R.D. Rowland's decision to invert the names calling the town "Wentworth" and the sinister house "Whyburn" suggests intentionality rather than coincidence.

Was R.D. Rowland making a statement about power and its abuses? About the way colonial families controlled not just land but narratives? About secrets hidden in grand houses on properties owned by Australia's would-be aristocrats?

These questions remain unanswered, but they continue to generate scholarly interest.

The identity of R.D. Rowland remains unknown.

The fate of Constance and Christian Marsh, whether they were real children who died tragically, fictional characters who lived only in an author's imagination, or something in between remains unknown.

Martindale House near Bourke still stands, now part of a larger property compound, its grand Colonial architecture looking increasingly out of place amongst more utilitarian modern buildings. The Wentworth family maintains ownership. Whatever secrets it may contain, if any, remain undisclosed.

And somewhere in New South Wales, perhaps in a cemetery near Bourke, perhaps elsewhere, perhaps nowhere, two graves may or may not mark the resting place of children named Constance and Christian, who may or may not have been the Furrow's Fixers, who may or may not have died in December 1938 after investigating something they should have left alone.

In the end, perhaps that is the most fitting legacy for a series about young detectives who prided themselves on solving mysteries: they became a mystery themselves, one that resists all attempts at resolution. The Furrow's Fixers solved their last case and disappeared into legend, leaving behind only ten books, a handful of clues, and the haunting possibility that some stories are true even when they cannot be proven.

Some doors, once opened, can never be properly closed again.

References and Archives

Primary Sources:

• The archives of Puggle Publishing House Co., including all surviving R.D. Rowland manuscripts, correspondence, and business records, are held by the State Library of Victoria (MS 13491). The original blue envelopes in which manuscripts arrived are preserved separately in climate-controlled storage and are available for viewing by appointment only.

• Herbert Wickham's personal papers, including diaries and correspondence (1905-1951), State Library of Victoria (MS 13492).

• Dorothy Ashton's papers, including correspondence with Dr. Margaret Sutherland and contributions to oral history projects, National Library of Australia (MS 9847).

• Edmund and Charles Doherty business correspondence and company records (1887-1926), State Library of Victoria (MS 13493).

Secondary Sources:

• Sutherland, Margaret (1978). "Pseudonymity and Authorship in Australian Children's Literature." PhD thesis, University of Melbourne. Available through University of Melbourne library system.

• Galloway, Peter (1976). "The Real Big Old Bush House?" The Australian, 23 October 1976. Available through National Library of Australia newspaper archives (Trove).

• Hartley, Edmund (1939). "The Cipher in the Nursery: R.D. Rowland's Rorschach Test for a Nation." The Adelaide Review, April 1939. Reprinted in various anthologies of Australian literary criticism.

• "Crackers and Corkers: Publishing Memories from the Puggle Years" (1967). Oral history project featuring interviews with Herbert Wickham, Dorothy Ashton, and former staff members. National Library of Australia Oral History Collection.

• "What Has Happened to Australian Children's Literature?" Editorial, The Sydney Morning Herald, 8 January 1940.

• Various articles on the Fixers scandal, The Melbourne Age, December 1939-February 1940.

Related Holdings:

• Property records relating to "Ploughman's Furrow" and Marsh family holdings, New South Wales Land Registry Services.

• Wentworth family papers (partial collection, MS 7293), Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales.

• Bourke Shire Council records, including cemetery records (partial, post-1952 fire), Bourke Local Studies Centre.

• Martindale House property records and correspondence, held privately by current owners; access restricted.

• Peter Galloway research notes and interview transcripts (presumed lost following his death in 1981).

Collections Containing Puggle Publishing Books:

• Complete run of Cracking Larks annual anthologies (1928-1940), State Library of Victoria.

• Furrow's Fixers series, first editions (1935-1939), National Library of Australia and various state libraries.

• Various Puggle Publishing House catalogues and promotional materials, State Library of Victoria.

The author of this article acknowledges that certain details regarding the Marsh family and the circumstances of 1938 remain unverified and should be treated as speculative pending further research. Researchers are encouraged to examine primary source materials and draw their own conclusions.