Puggle Publishing House Co.

Dorothy Ashton (Assistant Editor, 1931-1942)

Furrow's Fixers series

Puggle Publishing House Co. was an Adelaide-based Australian publishing company that operated from 1887 to 1942. Founded by brothers Edmund and Charles Doherty, the company initially focused on educational materials before becoming known for its children's literature, particularly the annual anthology Cracking Larks (1928-1940) and the controversial Furrow's Fixers mystery series (1934-1939).

The company's closure in 1942 was officially attributed to wartime economic pressures, though it had been severely damaged by the 1939 scandal surrounding the final Furrow's Fixers book, The Big Old Bush House, which was deemed inappropriate for children and led to widespread controversy.

- 1 History

- 1.1 Colonial Beginnings (1887-1914)

- 1.2 The Wickham Era (1914-1934)

- 2 The Furrow's Fixers Phenomenon

- 2.1 The Mysterious R.D. Rowland

- 2.2 Series Success (1934-1938)

- 3 The 1939 Scandal

- 3.1 Arrival of "The Big Old Bush House"

- 3.2 Scandal and Aftermath

- 3.3 The Mystery Deepens

- 4 Decline and Closure (1940-1942)

- 5 Legacy and Subsequent Research

- 5.1 The Whyburn House Connection

- 5.2 Theories and Speculation

- 6 Cultural Influence

- 7 References and Archives

History

Colonial Beginnings (1887-1914)

Puggle Publishing House Co. was established in Adelaide in 1887 by brothers Edmund and Charles Doherty, former compositors at The Advertiser newspaper who had harboured dreams of literary independence. The company name, taken from the colloquial term for a young echidna, was meant to evoke something distinctly Australian—though critics at the time found it rather undignified for a firm with serious aspirations.

The Doherty brothers initially focused on what Edmund termed "instructional literature for the improvement of colonial youth" which historians have deemed a rather grandiose description for cheaply produced pamphlets on topics ranging from basic arithmetic to moral comportment. These early publications were largely forgettable, though their 1889 volume "The Young Australian's Guide to Proper Penmanship" did enjoy modest success in South Australian classrooms.

The company's fortunes changed dramatically in 1893 when they secured the Australian rights to publish several popular British story papers. This arrangement proved lucrative enough to allow the Doherty brothers to move from their cramped offices above Birks' Chemist on Rundle Street to more respectable premises at 6 Rundle Street, close to the brother's respectable gentleman's association, The Adelaide Club. By the turn of the century, Puggle Publishing had established itself as a reliable, if unexceptional, presence in Australian publishing. At this point they were known primarily for school primers, agricultural guides, and the occasional novel of questionable literary merit.

Charles Doherty died in 1902 following a riding accident, leaving Edmund as sole proprietor. Edmund proved less interested in day-to-day operations than his brother had been, preferring to spend his time at the Adelaide Club discussing literature rather than producing it. He hired a young man named Herbert Wickham as managing editor in 1905, a decision that would ultimately reshape the company's trajectory.

The Wickham Era and the Birth of Cracking Larks (1914-1934)

Herbert Wickham was a peculiar fellow: short, bespectacled and possessed of an encyclopaedic knowledge of children's literature from around the world. Where Edmund Doherty saw publishing as a gentleman's vocation, Wickham saw it as both art and industry. He had grown up reading penny dreadfuls and serialised adventures, and he believed passionately that Australian children deserved their own homegrown stories rather than endless imports from Britain and America.

When the Great War began in 1914, Wickham found himself in charge of Puggle Publishing's operations, as Edmund had volunteered for service despite being well past the usual age (he served as an officer and never saw combat). Wickham used this opportunity to begin experimenting with original Australian content. His first venture was a series of pamphlets featuring bush legends and Aboriginal stories, respectfully adapted with consultation from Indigenous Elders. This was a progressive approach for the era, though one that sold poorly.

Undeterred, Wickham persevered. In 1920, he launched "The Young Australian's Story Paper," a monthly periodical featuring adventure stories, nature articles, and puzzles. It achieved moderate circulation, primarily in South Australia and New South Wales. More significantly, it established Puggle Publishing as a company interested in local talent.

Edmund Doherty returned from the war in 1919 and was bewildered by the changes Wickham had implemented, and promptly retired to his country property near Glenelg, leaving Wickham complete creative control. Edmund died in 1926, and his will revealed that he had, somewhat carelessly, never updated his business succession plans. The company passed to a distant cousin in the Barossa Valley who had no interest in publishing and was happy to let Wickham continue running things in exchange for a share of profits.

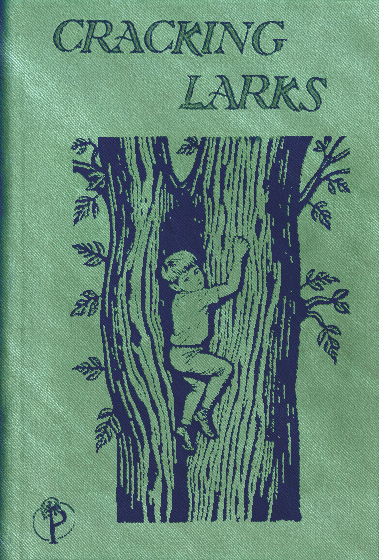

The true masterstroke came in 1928 when Wickham conceived of an annual anthology aimed at young readers aged eight to fourteen. He wanted something that felt like an event, a book that children would anticipate each year, that parents would purchase as a reliable Christmas gift, that would become a fixture of Australian childhoods. After considerable deliberation (and several rejected titles including "The Young Australian's Annual" and "Bush Tales and Adventures"), he settled on Cracking Larks—a name that captured the energetic, optimistic spirit he hoped to convey.

The first edition of Cracking Larks, published in November 1928, was a handsome volume bound in deep green cloth. It contained a mixture of adventure stories, natural history articles, puzzles, and illustrations by some of Adelaide's better commercial artists. Wickham had solicited contributions from established Australian authors as well as promising newcomers, and he'd insisted on paying rates comparable to what British publications offered. This approach earned him loyalty from his numerous contributors.

Cracking Larks 1928 sold respectably but not spectacularly, enough to justify a second edition. The 1929 edition did better still. By 1931, Cracking Larks had become a minor institution, with children writing letters to Puggle Publishing House throughout the year suggesting story ideas and asking when the next volume would appear.

The anthology's success allowed Wickham to expand Puggle's operations. He hired additional staff, including a sharp young woman named Dorothy Ashton as assistant editor in 1931. This move was scandalous in some circles, though Wickham defended the appointment by noting that women were the primary purchasers of children's books and might therefore have valuable insights into what sold. He also began publishing standalone novels by authors who had first appeared in Cracking Larks, creating something of a literary proving ground for future projects.

The Furrow's Fixers Phenomenon

The Mysterious R.D. Rowland

The 1934 edition of Cracking Larks was in production during the winter months of that year, with Wickham and Ashton reviewing submissions in their Rundle Street offices. The anthology had become a well-oiled machine by this point, with regular contributors and a reliable stable of artists. Most submissions arrived through the post in the conventional manner, occasionally delivered by hand by Adelaide-based writers.

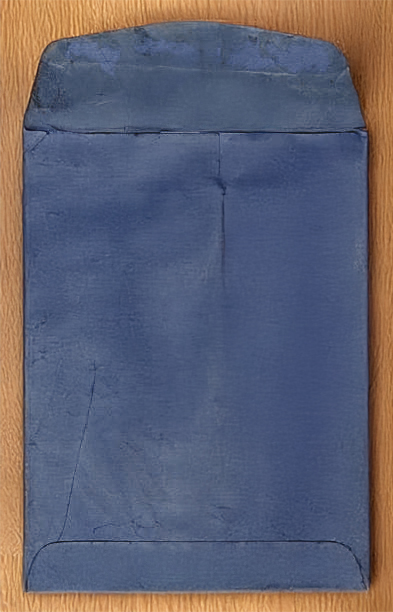

It was therefore somewhat unusual when, on a grey morning in June 1934, a manuscript arrived in a blue envelope with no return address. The postmark indicated it had been sent from somewhere in New South Wales, though the exact location was smudged and illegible. Inside was a handwritten story titled "Furrow's Fixers and the Case of the Missing Cake," authored by one R.D. Rowland.

Dorothy Ashton later recalled in a 1967 interview for the oral history project "Crackers and Corkers: Publishing Memories from the Puggle Years" that the handwriting itself was remarkable "almost calligraphic in its precision, yet, I'm not sure how to say it but urgent, as though written in great haste by someone trained in excellent penmanship." The manuscript was accompanied by no cover letter, no biographical note, no contact information beyond a single line at the bottom of the final page: "Further correspondence may be directed to R.D. Rowland, care of Puggle Publishing House." but no address was listed here either. The note, Ashton thought, was rather presumptuous.

The story itself was charming: a light mystery involving twin children, Constance and Christian Marsh, who lived on a property called Ploughman's Furrow near a fictional bush town called Wentworth. The twins were nine years old in the story, and the case they solved (the theft of their mother's cake from a CWA bake sale by a jealous rival named Mrs. Abernathy) was delightfully small-scale yet treated with the gravity of a major crime. The writing had an authentic voice. It was distinctly Australian in setting and vernacular, yet with echoes of the popular British adventure stories that dominated children's reading.

Wickham was immediately taken with it. He'd been hoping to include more serialisable characters in Cracking Larks—the anthology format made it difficult to build reader loyalty to recurring personalities. Here was a perfect opportunity: child detectives in a recognisable Australian setting, solving problems that felt real to young readers. He accepted the story for Cracking Larks 1934 and sent a letter to "R.D. Rowland, care of Puggle Publishing House" expressing his enthusiasm and inquiring whether the author might be interested in submitting additional stories.

The letter was filed in Puggle's incoming correspondence, where it remained unclaimed. No R.D. Rowland ever appeared to collect it.

Series Success (1934-1938)

Cracking Larks 1934 was published in November of that year and sold better than any previous edition. While it would be an exaggeration to credit the Fixers story entirely for this success readers' letters made clear that Constance and Christian Marsh had struck a chord. Children wrote asking for more Fixers stories. Parents mentioned the characters favourably in letters praising the anthology. One reviewer in The Advertiser specifically singled out "the delightful Marsh twins" as exemplifying the kind of Australian characters young readers deserved to see more of.

Wickham immediately wrote to R.D. Rowland (again, care of the publishing house) expressing hope that more Fixers stories might be forthcoming and suggesting that a series of standalone books might be commercially viable. This letter, like the first, went unclaimed.

Then, in December 1934, another blue envelope arrived.

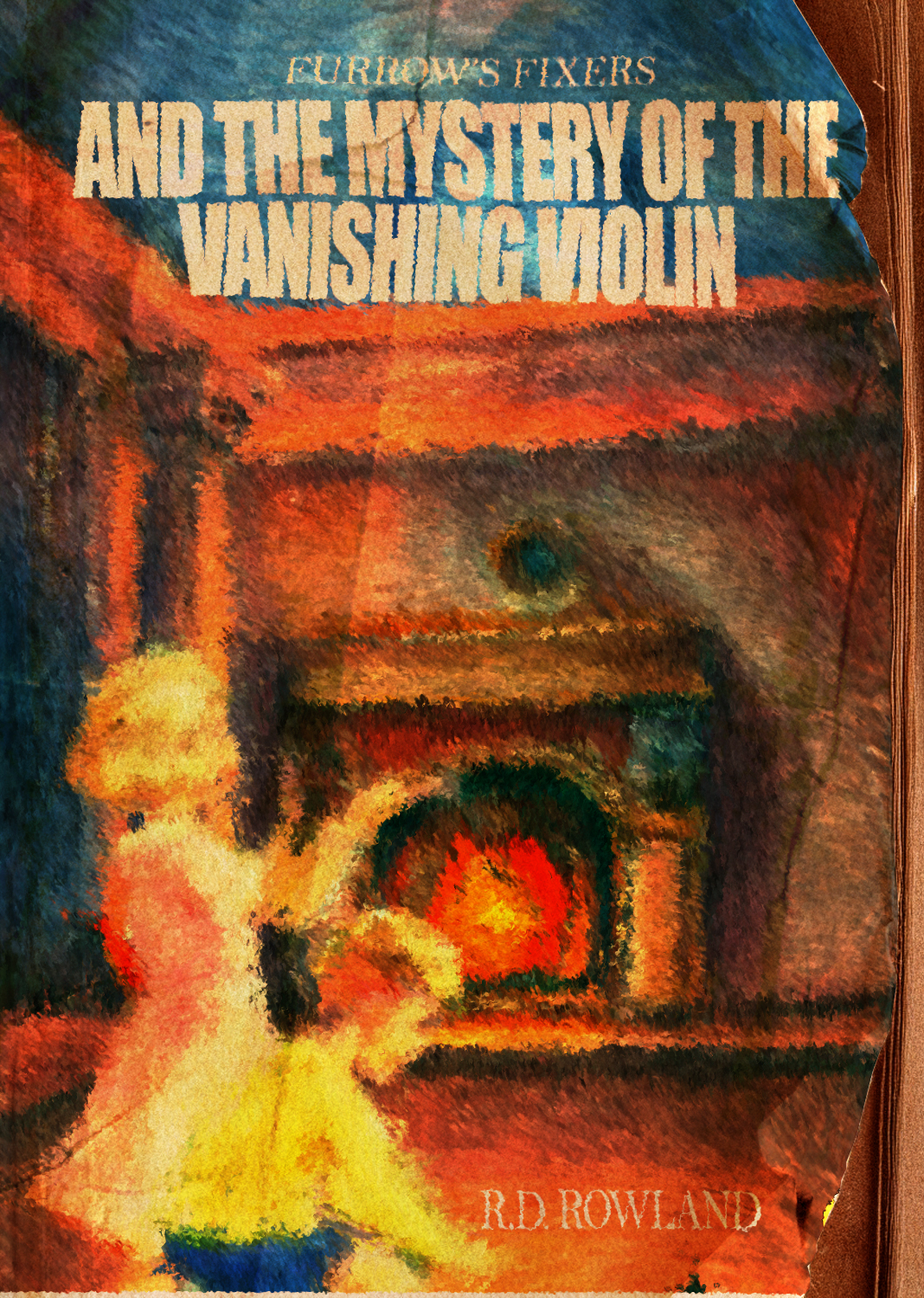

Inside was a complete manuscript for a novel titled "Furrow's Fixers and the Mystery of the Vanishing Violin." It was considerably longer than the Cracking Larks story at approximately 35,000 words. This novel featured the Marsh twins, now aged eleven, investigating the theft of a valuable instrument from their music teacher during the Christmas holidays. The story was expertly plotted, with genuine clues, red herrings, and a satisfying resolution. Once again, there was no cover letter, no biographical information, just the byline R.D. Rowland and that single line directing correspondence to Puggle Publishing House.

Wickham discussed the manuscript with Dorothy Ashton. Both agreed it was publication-worthy, but both were also troubled by the author's anonymity. According to their later accounts in "Crackers and Corkers," Ashton suggested rejecting it on principle, to which Wickham responded, "We could... But it would be a damned shame. It's good, Dorothy. Really quite good." After considerable deliberation, they decided to proceed with publication despite the irregularity.

They prepared a contract offering standard terms and addressed it to "R.D. Rowland, care of Puggle Publishing House." In a baffling turn, the signed contract arrived three weeks later in another blue envelope, with bank details for an account at the Bank of New South Wales in Bathurst—concrete evidence that R.D. Rowland was a real person, yet one who remained determinedly anonymous.

"Furrow's Fixers and the Mystery of the Vanishing Violin" was published in April 1935. Puggle Publishing marketed it modestly, as they were still primarily known for Cracking Larks and their educational books. The book sold steadily if not spectacularly through autumn and winter. Interestingly, the story made reference to bore baths in the fictional town of Wentworth, a detail that would later prove significant to researchers investigating the series' geographical basis.

Then, in June 1935, another blue envelope arrived containing "Furrow's Fixers and the Secret of the Scribbly Gum."

A pattern was establishing itself: two manuscripts per year, arriving like clockwork in June and December, each in an identical blue envelope, each featuring the Marsh twins solving mysteries during their school holidays. Wickham attempted numerous times to establish contact with R.D. Rowland through letters sent to the bank in Bathurst (which were returned as undeliverable), through notices placed in regional New South Wales newspapers (which went unanswered), and even through a half-hearted attempt to have Dorothy Ashton travel to Bathurst to investigate (which she sensibly declined, pointing out that hunting down a pseudonymous author who clearly valued privacy was both impractical and possibly unethical).

Wickham eventually accepted the situation's peculiarity and focused on the commercial opportunity. Each Fixers book was released six months apart, April and December, timed to coincide with Easter and Christmas holidays, just like the stories themselves. This proved brilliantly effective marketing. Children who'd read about the Marsh twins' Christmas adventures could immediately experience their Easter adventures, creating a sense of real-time continuity.

The books' popularity grew steadily. By 1936, the Fixers series was Puggle Publishing's bestselling line. Constance and Christian Marsh appeared on the covers of Cracking Larks editions. Fan letters arrived addressed to the Marsh twins care of Puggle Publishing House. Schools incorporated the books into their libraries. Parents discovered they made reliable gifts.

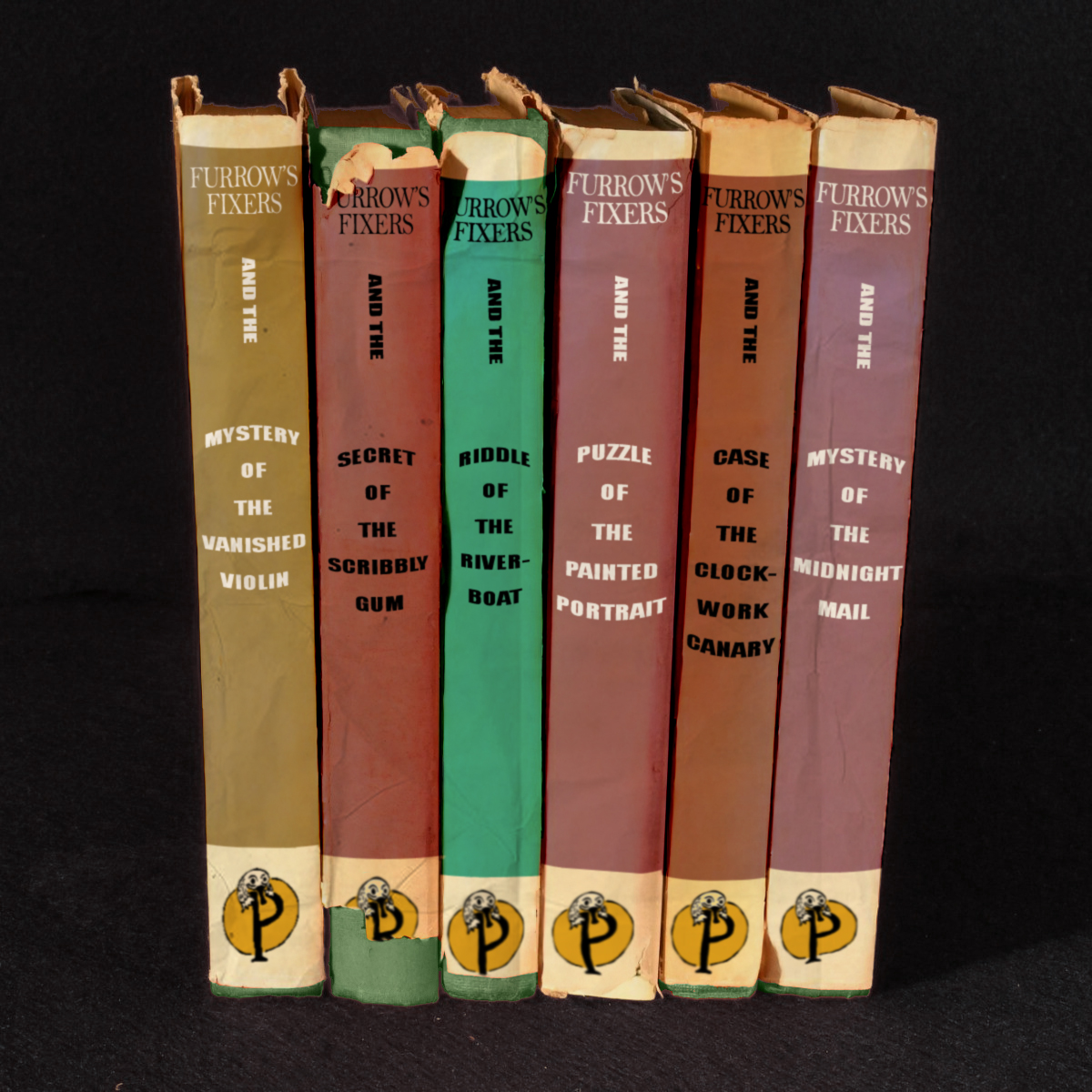

The titles during this period included:

- "Furrow's Fixers and the Mystery of the Vanishing Violin" (April 1935)

- "Furrow's Fixers and the Secret of the Scribbly Gum" (December 1935)

- "Furrow's Fixers and the Riddle of the Riverboat" (April 1936)

- "Furrow's Fixers and the Puzzle of the Painted Portrait" (December 1936)

- "Furrow's Fixers and the Case of the Clockwork Canary" (April 1937)

- "Furrow's Fixers and the Mystery of the Midnight Mail" (December 1937)

- "Furrow's Fixers and the Adventure of the Ancient Map" (April 1938)

- "Furrow's Fixers and the Enigma of the Empty Estate" (December 1938)

- "Furrow's Fixers and the Treasure of the Mysterious Rover" (April 1939)

Each story maintained the series' winning formula: the Marsh twins returning from their respective boarding schools, catching up on local news, engaging in their characteristic "troving" (researching at libraries, museums, and archives), and ultimately solving mysteries that ranged from the whimsical to the genuinely intriguing. The books were wholesome without being preachy, Australian without being self-consciously nationalistic, and clever without being condescending.

R.D. Rowland's identity remained a mystery, albeit one that Puggle Publishing had learned to leverage. Advertisements for the books played up the enigmatic author: "Written by the mysterious R.D. Rowland! Who are they? Where are they? Only the Fixers might be able to solve that mystery!" It was good marketing, and it sold books.

Herbert Wickham, now in his fifties and increasingly content to let Dorothy Ashton handle much of the editorial work, had reason to be satisfied. Puggle Publishing was thriving. Cracking Larks remained popular. The Fixers series had established the company as a significant player in Australian children's literature. Everything was proceeding exactly according to plan.

Until December 1939.

The 1939 Scandal

Arrival of "The Big Old Bush House" (September 1939-December 1939)

The blue envelope that arrived in September 1939 seemed no different from the nine that had preceded it since the series' inception. It was the expected weight, the expected size, postmarked from somewhere in New South Wales (the postmark was, as always, conveniently illegible). Dorothy Ashton opened it at her desk on a warm afternoon, expecting another wholesome mystery adventure.

What she found instead would haunt Puggle Publishing for years to come.

The manuscript was titled "Furrow's Fixers and the Big Old Bush House," and it began conventionally enough. The Marsh twins, now fourteen years old, returned to Ploughman's Furrow for the Christmas holidays. They heard about a mysterious newcomer to the area—a Mr. Thornton Grice who had moved into the long-abandoned Whyburn house on Settler's Ridge. They began investigating, troving at the library, uncovering clues about the house's former owner, Ephraim Whyburn, and his hidden collection of antiquities.

So far, entirely in keeping with the series' established pattern.

But approximately one-third of the way through the manuscript, something shifted. The tone darkened. The story that had seemed like a straightforward mystery about treasure hunting began to veer into territory that Dorothy Ashton found increasingly disturbing. By the time she reached the final page, she felt physically ill.

She immediately took the manuscript to Herbert Wickham. Wickham read it that evening and returned to the office the next morning looking haggard. According to their accounts in "Crackers and Corkers," Wickham stated simply, "We can't publish this," to which Ashton agreed emphatically. The oral history records that both editors were deeply shaken by the manuscript's content and spent considerable time debating what action to take.

The question was what to do. R.D. Rowland had never failed to deliver a manuscript on schedule. Readers were expecting the next Fixers adventure in December 1939. Contracts with booksellers had been signed. Advertisements had been placed. Children across Australia were anticipating the Marsh twins' next adventure.

Wickham composed a letter, the most carefully worded letter of his career, explaining that the submitted manuscript was unsuitable for publication and requesting that R.D. Rowland submit a replacement. He detailed the specific objections (in language sufficiently vague that the letter itself wouldn't be inappropriate should anyone else read it) and emphasised that Puggle Publishing had always valued their relationship with R.D. Rowland and hoped it would continue with material more in keeping with the series' established character.

This letter was sent to the Bank of New South Wales in Bathurst, to the "care of Puggle Publishing House" address (despite knowing it would go unclaimed), and even, in a fit of desperation, as a notice in the classified sections of newspapers throughout regional New South Wales: "R.D. Rowland: Please contact Puggle Publishing regarding recent submission. Urgent."

No response came.

October 1939 passed. November arrived. Wickham and Ashton faced an impossible situation. They had no manuscript, no way to contact their author, and an increasingly anxious network of booksellers and distributors asking about the December publication. As documented in Ashton's personal papers, she suggested various alternatives including commissioning a ghostwriter or reissuing an earlier book, all of which Wickham rejected as either fraudulent or commercially unviable.

Then, in mid-November, a letter arrived. It was not in the usual blue envelope. It was in a plain manila envelope, postmarked from Sydney, written in a different hand—scratchy and hurried rather than elegantly calligraphed. It was addressed to Herbert Wickham personally.

The letter was unsigned, but its content was unambiguous:

According to "Crackers and Corkers," Wickham and Ashton stared at this letter in stunned silence before Ashton identified it as coming from R.D. Rowland, telling them "to either publish that... that thing... or publish nothing at all." The oral history records several days of agonised deliberation, with Wickham developing what Ashton described as "a peculiar obsession with the question of why" an author would deliberately sabotage a successful series.

After considerable internal debate involving printers, lawyers, and accountants, Wickham made his controversial decision. Puggle Publishing would release "Furrow's Fixers and the Big Old Bush House" exactly as submitted, with only minimal copyediting, but in a limited run of just 500 copies with no advertising campaign. Dorothy Ashton argued strenuously against this plan and was overruled—an experience she would later note bitterly was "one of the inevitable experiences of being a woman in publishing."

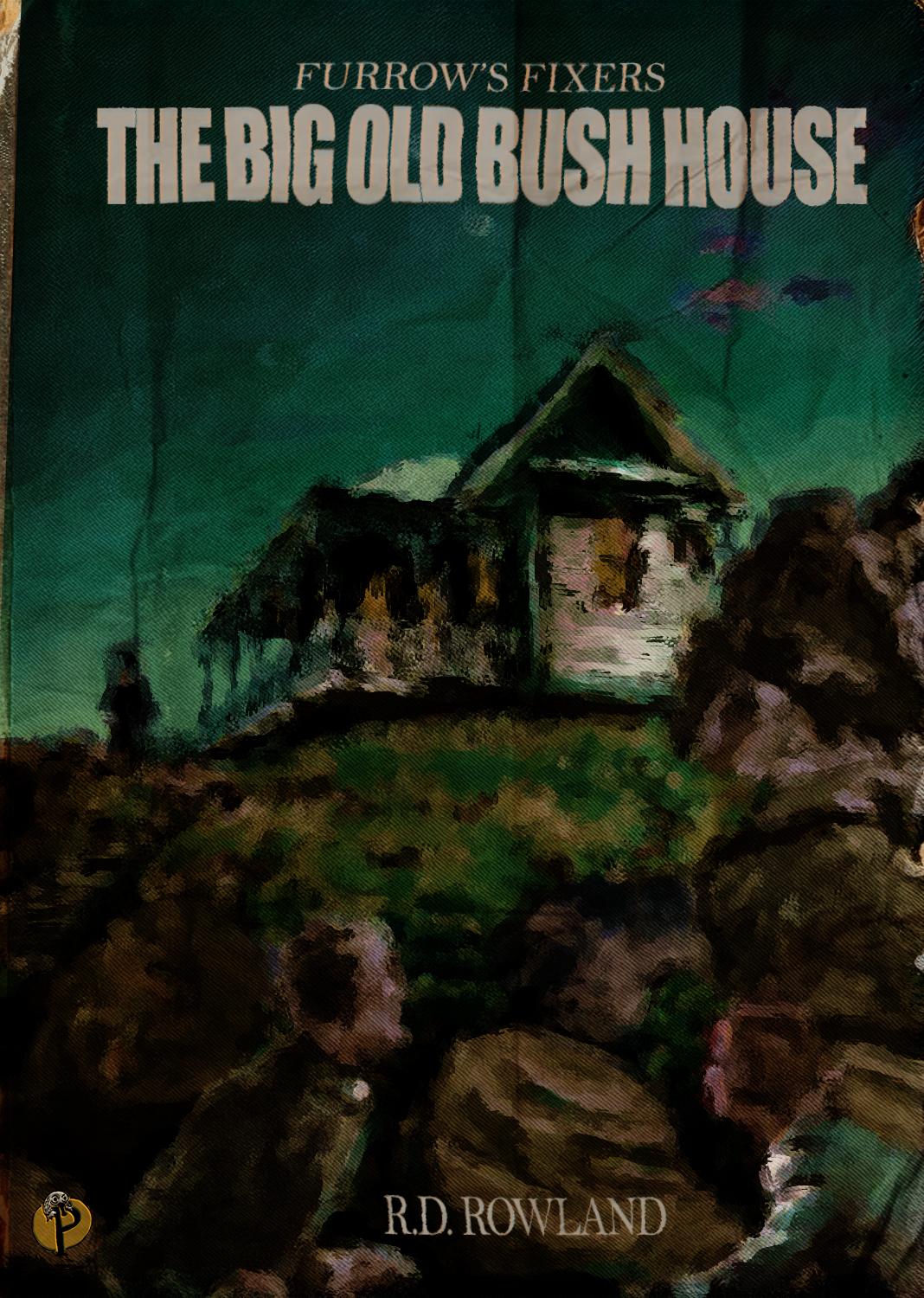

"Furrow's Fixers and the Big Old Bush House" was published in December 1939 (though as a side note the book's cover just read 'Furrow's Fixers The Big Old Bush House' leaving the and off, the and is present on the spine of the book and as it matches the naming pattern of the rest of the series "Furrow's Fixers and the Big Old Bush House" is considered the official title).

Scandal and Aftermath (December 1939-June 1940)

The first hint that something was wrong came not from outrage, but from confusion. A bookseller in Newcastle telephoned Puggle Publishing asking if there had been a printing error—surely the book couldn't end like that? Similar calls followed from Sydney, Canberra, Adelaide. Not anger, but bewilderment.

Then the letters began arriving. From parents whose children were upset by the ending. From school librarians uncertain whether to shelve it with the other Fixers books. From teachers asking how to discuss the book with students who had questions they couldn't answer. The tone was less accusatory than baffled: what had R.D. Rowland been thinking?

The issue, as reviewers and parents quickly identified, was not that the book was overly obscene or violent in any conventional sense, though its content did seem inconsistent with the target audience. The problem was also structural and tonal—a violation of the unspoken contract between children's literature and its readers.

Previous Fixers adventures had concluded with mysteries solved, order restored, and the Marsh twins safely back at Ploughman's Furrow awaiting their next adventure. "The Big Old Bush House" offered no such comfort. The ending was ambiguous. Questions remained unanswered. The twins seemed changed by their experience in ways the book didn't fully explain or explore. And the final two words of the text—which many readers found inexplicably more disturbing than anything that came before—suggested that some things could not be fixed, even by the Furrow's Fixers.

For readers accustomed to tidy resolutions and reassuring endings, this was profoundly unsettling. It violated the genre's fundamental promise: that children would be safe, that mysteries would be solved, that the world could be put right.

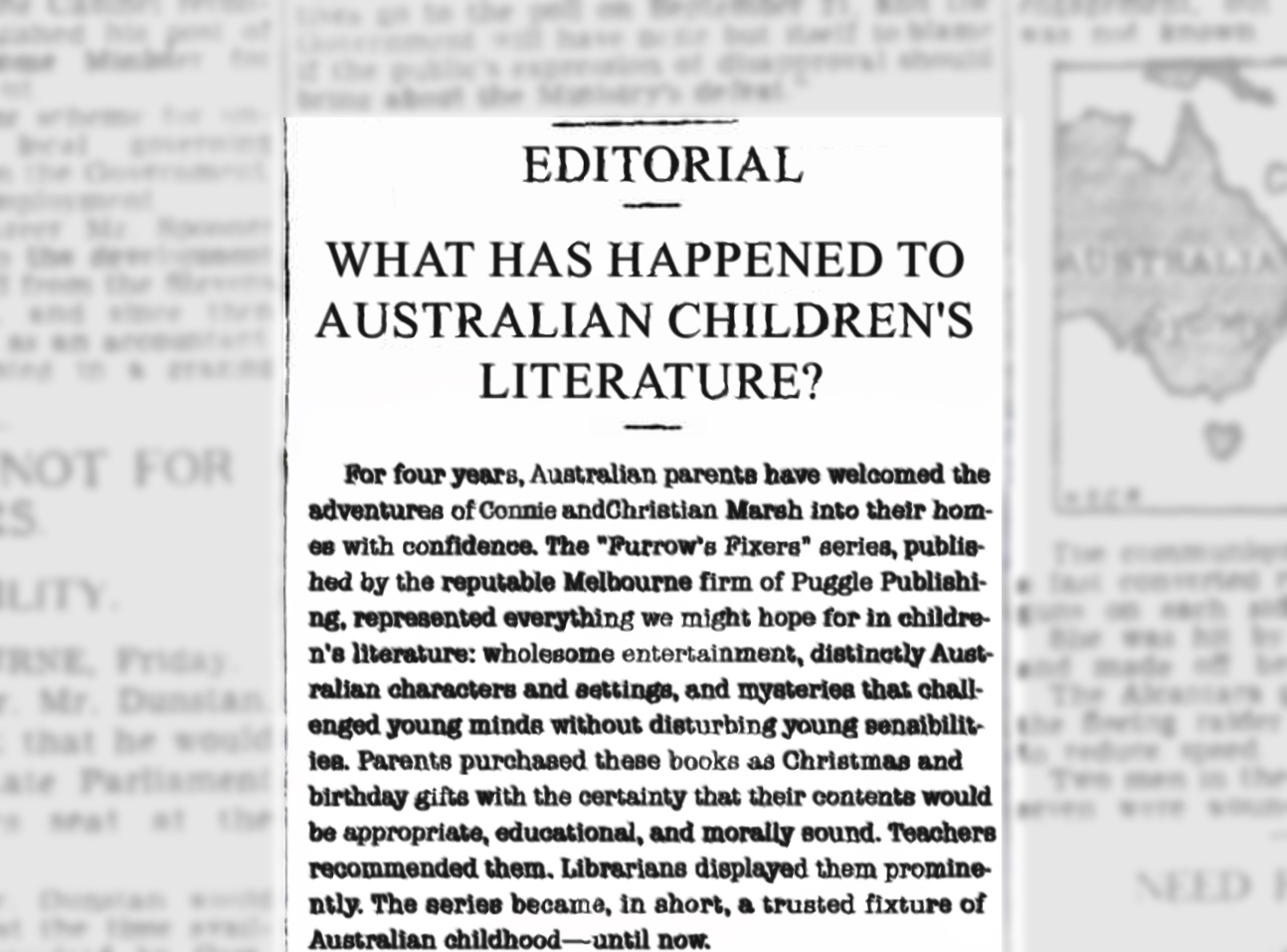

Reviews reflected this confusion more than outrage. The Sydney Morning Herald ran an editorial titled "What Has Happened to Australian Children's Literature?" that began by praising the series' four-year run before expressing bewilderment at the final installment. The editorial went on to emphasise that the issue was not impropriety but form: "The problem is not that Mr. Rowland has written something inappropriate, but that he has written something unsuitable for the audience he has cultivated. Children who have come to trust the Furrow's Fixers series now find themselves confronted with an ending that provides no resolution, no comfort, and no clear moral lesson. This is not a failure of artistry but a failure of judgment about what children's literature ought to provide."

The Advertiser was more measured but equally puzzled: "One must wonder what R.D. Rowland intended by this conclusion. The book is competently written, but it violates the implicit contract between author and young reader."

A school librarian wrote to Puggle Publishing: "My students are asking what happened to the Roberts boy. They want to know if the Marsh twins are all right. I don't know what to tell them. A children's book should provide answers, not more questions."

A mother from Adelaide complained: "My daughter has read every Fixers book twice. She couldn't sleep after finishing this one. Not from nightmares, though she's had those too, but from worry. She keeps asking me what happens next. I don't know what to tell her."

But here was the commercial disaster: Wickham had only printed 500 copies. He'd known the book was wrong for the audience and had minimised his risk. This meant that when booksellers began receiving complaints and requests for the book, they had nothing to sell. The controversy, such as it was, revolved as much around the book's unavailability as its content.

Parents who'd heard about the "troubling" Fixers book wanted to read it themselves before deciding if it was appropriate. Critics who'd heard about the controversy wanted copies to review. Collectors sensed something valuable. But there were only 500 copies, most already sold or returned.

Booksellers were frustrated. "We have customers asking for the new Fixers book," one wrote to Puggle Publishing, "and we have none to sell them. Meanwhile, we're returning the copies we do have because parents find them unsuitable. This is terrible business."

The real damage to Puggle Publishing wasn't moral outrage—it was the appearance of incompetence. They'd published a book nobody wanted in quantities nobody could buy. They'd ended their most successful series with an installment that violated audience expectations. They'd demonstrated poor editorial judgment and worse commercial sense.

The Advertiser published an article titled "The Mysterious Ending of the Furrow's Fixers" that was more curious than condemning. It detailed the series' success, R.D. Rowland's anonymity, and the puzzling final book. Several enterprising journalists attempted to track down R.D. Rowland, but their investigations led nowhere.

There were some—mostly older readers and literary critics—who defended the book. Letters arrived at Puggle Publishing praising "The Big Old Bush House" as a mature, sophisticated work that took young readers seriously. Several reviewers suggested that R.D. Rowland had deliberately subverted the adventure genre to make a point about the world's complexity.

"The book," wrote one critic in the very first edition of Meanjin Quarterly, "is not inappropriate because it is improper. It is inappropriate because it refuses to lie. It tells children that not everything can be fixed, that some mysteries have no solutions, that growing up means accepting ambiguity. That may not be what we want children's literature to do, but perhaps it's what it should do."

This defense made little commercial difference. The Fixers series was finished. Even if R.D. Rowland submitted a new manuscript, booksellers were wary. The brand had been damaged by the appearance of editorial misjudgment.

Most devastating was the silence from schools and libraries—the institutional buyers who had made the series profitable. They didn't demand the book be banned or burned. They simply declined to purchase it. It was unsuitable for their purposes. That was judgment enough.

Wickham found himself in an impossible position. He couldn't satisfy those who thought he shouldn't have published the book at all, nor those who thought he should have printed more copies and defended it more vigorously. He'd tried to honor his commitment to R.D. Rowland while protecting his business, and had succeeded at neither.

The Mystery Deepens (July 1940)

In July 1940, as the controversy was finally beginning to fade from public consciousness, another blue envelope arrived at Puggle Publishing House.

Dorothy Ashton opened it with a sense of profound dread.

Inside was a brief handwritten note:

R.D. Rowland"

There was no manuscript. Just this cryptic farewell.

As Ashton later recalled in a 1971 letter to Dr. Margaret Sutherland, she showed the note to Wickham and they sat in silence for a long moment. "Do you think they're real?" she asked finally. "The twins. Do you think Constance and Christian Marsh actually existed?" Wickham dismissed the suggestion, but Ashton noted that "his voice lacked conviction." She continued to wonder whether R.D. Rowland had been "writing from life" and whether they had been "publishing someone's testimony disguised as children's fiction."

Wickham placed the note in a file marked "R.D. Rowland Correspondence"—a file that contained mostly returned letters and unanswered queries.

No further communication ever arrived from R.D. Rowland.

Decline and Closure (1940-1942)

The scandal surrounding "The Big Old Bush House" damaged Puggle Publishing irreparably. The 1939 edition of Cracking Larks sold poorly. The 1940 edition sold even worse. Booksellers who'd once prominently displayed Puggle's books now relegated them to back shelves or declined to stock them entirely.

The war didn't help. As Australia mobilised, paper became scarce, distribution networks were disrupted, and public attention focused on matters more pressing than children's literature. Several of Puggle's staff enlisted or took positions in war-related industries. Herbert Wickham, now in his sixties and exhausted by the Fixers debacle, seriously considered retirement.

In 1941, Puggle Publishing released only three books, a far cry from their productive years in the mid-1930s. Cracking Larks was discontinued after the 1940 edition, ending a tradition that had lasted twelve years.

Dorothy Ashton left in early 1942 to take a position with Angus & Robertson, one of Puggle's larger competitors. In her farewell letter to Wickham, she wrote:

Wickham closed Puggle Publishing House in August 1942. The official reason given was "wartime economic pressures," which was true enough. The unofficial reason was that Wickham had lost his enthusiasm for the business, haunted by questions he couldn't answer and decisions he couldn't unmake.

The company's backlist was sold to various publishers. Its archives (including all correspondence, contracts, and manuscripts) were donated to the State Library of South Australia, where they remain available to researchers, though few have examined them in detail. The original manuscripts in R.D. Rowland's distinctive handwriting are stored in climate-controlled conditions, pristine and inexplicable.

Herbert Wickham retired to Brighton and died in 1951, never having given a public interview about the Fixers scandal. In his personal papers, donated to the State Library after his death, there is a single notation in a diary entry from December 1939:

Legacy and Subsequent Research

In the decades since Puggle Publishing's closure, the Furrow's Fixers series has become a footnote in Australian literary history. It is remembered, if at all, primarily for its scandalous conclusion rather than its four years of wholesome success. The first nine books occasionally appear in antiquarian bookshops, modestly priced and rarely purchased. "The Big Old Bush House," by contrast, has become a collector's item, with surviving copies fetching substantial sums from collectors of curiosa and literary scandal. Strangely, though the book has never been officially reprinted, it remains the most sought-after volume in the series.

Several researchers have attempted to identify R.D. Rowland, without success. The most thorough investigation, conducted by Dr. Margaret Sutherland for her 1978 doctoral thesis "Pseudonymity and Authorship in Australian Children's Literature," concluded that R.D. Rowland was likely a single individual rather than a collective pseudonym, probably female (based on handwriting analysis and certain stylistic elements), probably living in rural New South Wales, and probably someone with either personal experience of the region described in the books or access to detailed information about it.

But beyond these tentative conclusions, R.D. Rowland's identity remains unknown.

There is, however, one curious footnote to Dr. Sutherland's research. While investigating property records in regional New South Wales, she discovered that a property named "Ploughman's Furrow" had indeed existed near the town of Bourke not the fictional "Wentworth" of the books, but a real town in the northwest of the state. The property was registered to a family named Marsh.

Dr. Sutherland attempted to trace the Marsh family's history but encountered frustrating dead ends. Records showed that the property was sold in 1939 (the same year "The Big Old Bush House" was published) to a distant relative who subsequently subdivided and sold the land. The original homestead was demolished in 1947. Electoral rolls and census records confirmed that a family named Marsh had lived at the property during the 1920s and 1930s, and that this family had included at least two children, but beyond these basic facts, information was scarce.

Most intriguingly, Dr. Sutherland discovered that the local cemetery had contained two graves side by side, dated 1934, belonging to individuals identified only by their given names: Constance and Christian. The surnames on the headstones had weathered to illegibility, and cemetery records from that period had been lost in a fire in 1952.

Dr. Sutherland included this information as an appendix to her thesis but cautioned against drawing definitive conclusions. "The coincidence of names and location is striking," she wrote, "but coincidences do occur. Without additional evidence, we cannot determine whether R.D. Rowland was writing fiction inspired by real people and places, or whether the parallels are simply artefacts of research and imagination."

She did, however, note one detail that she found "disquieting": the dates on the cemetery headstones indicated that Constance and Christian had died in June 1934, about the time that "Furrow's Fixers and the Case of the Missing Cake" was published.

The Whyburn House Connection

There is one final element to this story that deserves mention, though it strays from publishing history into something more speculative and historically significant.

In 1976, a journalist named Peter Galloway wrote an article for The Australian titled "The Real Big Old Bush House?" In it, he described travelling to the Bourke district in New South Wales and investigating the historical connections between R.D. Rowland's fictional "Wentworth" and the real town of Bourke.

What Galloway discovered was both fascinating and unsettling.

The fictional town in the Fixers series was called "Wentworth" a name that appeared repeatedly throughout the books as the setting for the Marsh twins' adventures. This seemed like a simple authorial choice, perhaps inspired by the well-known Wentworth family of Australian colonial history, or by one of the several towns named Wentworth across Australia.

But Galloway's research revealed something more intriguing: near Bourke, there stood (and still stands) a grand old house known locally as Pioneer's Light, built in the late nineteenth century. This house had been owned throughout its history by members of the Wentworth family specifically, distant relatives of the descendants of William Charles Wentworth, the explorer and statesman who had been instrumental in the attempts to establish an Australian aristocracy in the colonial period.

Pioneer's Light itself is remarkable: a substantial two-storey building in the Colonial style, considerably more elaborate than most bush homesteads of its era, suggesting the wealth and social aspirations of its owners. Over the decades, the property expanded, with additional buildings constructed around the original house in a more utilitarian, modern style. By the 1970s, when Galloway visited, Pioneer's Light formed the centrepiece of what had become a larger compound, with the grand old residence looking somewhat incongruous amongst its newer, hastier neighbours.

The house's association with the Wentworth family and through them, with Australia's brief flirtation with establishing a colonial aristocracy gave it a peculiar historical weight. The Wentworths had been amongst those who advocated for hereditary titles and formal class structures in the Australian colonies, proposals that were ultimately rejected in favour of more egalitarian principles. The family's mansions and estates scattered across New South Wales stood as monuments to this failed aristocratic dream.

What made this relevant to the Fixers mystery was the uncanny parallel: in R.D. Rowland's final book, the mysterious and sinister "Whyburn house" sat on Wentworth's Ridge overlooking the fictional town of Wentworth. In reality, a grand house (Pioneer's Light) existed near Bourke, owned by a family named Wentworth.

The reversal seemed deliberate as if R.D. Rowland was making some kind of statement about the relationship between names, places, and power. Was the fictional "Wentworth" a stand-in for Bourke? And if so, what was R.D. Rowland saying by naming the town after the family that owned the real house?

Galloway noted several other correspondences between R.D. Rowland's fictional Wentworth and the real Bourke:

- The books mention "Richard Street" as a main thoroughfare in Wentworth. Bourke has a Richard Street, where the town's war memorial stands matching a description in one of the early Fixers books.

- In "The Secret of the Scribbly Gum" the children are shown Fort Wentworth by Mr. Peters on a troving expedition, this site is reminiscent of Fort Bourke: the colonial stockade that a replica of stands today.

- The fictional Wentworth has a post office that features prominently in several stories, described with specific architectural details including "fruit trees in the front courtyard." Bourke's post office, a handsome building from the Federation period, matches this description almost exactly.

- The bakery in Wentworth is named "Morel's" the, over a century old, bakery in Bourke is named "Morrall's".

- On a troving trip in "Puzzle of the Painted Portrait" the twins pass the graves of several "Ghans" the text reads "The elaborate graves lined perpendicular to the others, facing in the direction of their god". This seems to be a reference to the graveyard in Bourke's many graves of Afghan Cameleers who were buried facing Mecca.

- There are streets mentioned throughout all the books that reflect the civic layout of the town.

- The bore baths mentioned in "The Mystery of the Vanishing Violin" correspond to Bourke's actual bore baths, a distinctive local feature.

Several minor characters in the books: shopkeepers, clergymen, town officials and more all have names that appear in Bourke's historical records from the 1930s, though whether these are deliberate references or coincidences is impossible to determine.

Most tellingly, the description of the Whyburn house in R.D. Rowland's final book closely matches Pioneer's Light: a two-storey Colonial structure with wide verandas and elaborate iron lacework, sitting on elevated ground overlooking the surrounding countryside.

Galloway interviewed several elderly residents of the Bourke area who remembered the 1930s. One woman, identified only as "Mrs. E.," claimed to recall a family named Marsh who had lived on a property near Bourke during that period.

"There were two children," Mrs. E. told Galloway. "Twins, I believe. Brother and sister. They went away to school, came back for holidays. Studious types, always at the library, always asking questions about local history. The girl was particularly clever she had a mind like a steel trap."

When asked what happened to the family, Mrs. E.'s account became vaguer. She mentioned "something tragic" in late 1939, around Christmas time. "There was an accident of some kind. Both children went missing. The family left soon after [...]couldn't bear to stay, I suppose. It was all very hushed up. Some things people don't like to talk about."

Galloway also discovered that in the late 1930s, Pioneer's Light had been leased to a Melbourne gentleman with interests in antiquities and Eastern mysticism. This gentleman arrived in 1938 and departed rather suddenly in early 1940. Local records show he paid his lease through the end of the year despite leaving early, and that there was some kind of incident at the property in December 1939 that required police attendance, though the nature of the incident was not recorded in available documents.

Galloway's article concluded with a provocative suggestion: that R.D. Rowland's stories were not entirely fiction, but rather a disguised account of real events, with names and details altered just enough to provide plausible deniability. The fictional town of "Wentworth" was Bourke. The Whyburn house was Pioneer's Light. And Constance and Christian Marsh were real children who died investigating something connected to that house and the powerful family who owned it.

"If this is true," Galloway wrote, "then 'Furrow's Fixers and the Big Old Bush House' was not a children's adventure gone wrong, but a testimony—a record of something dark that happened in December 1939, published in a way that everyone would dismiss as unsuitable fiction."

Reception and Criticism of Galloway's Theory

Galloway's article generated modest interest but was largely dismissed as speculative journalism. Critics pointed out numerous problems with his thesis:

- No death certificates could be located for Constance and Christian Marsh matching the details he described

- "Mrs. E." was never identified and could not be located for follow-up interviews

- The parallels between fictional Wentworth and real Bourke could easily be explained by authorial research rather than personal experience

- The idea that a powerful family would "hush up" deaths of children was melodramatic speculation without evidence

- When the Bourke cemetery records were checked (those that survived the 1952 fire), no graves matching the description could be definitively confirmed as belonging to children named Constance and Christian Marsh

Several members of the Wentworth family wrote letters to The Australian expressing displeasure at Galloway's insinuations. They distanced themselves from the branch near Bourke, suggesting they were distant relations at best. Galloway published a brief clarification that he had made no specific accusations and was merely exploring historical curiosities.

The article generated modest discussion then faded from public consciousness. Galloway continued his journalism career, covering various stories across regional Australia until his retirement in the late 1990s.

However, something curious happened to Galloway's relationship with the story. When contacted by researchers in the 2020s about his 1976 article and asked if he would consider writing an afterword for a new edition of "The Big Old Bush House," Galloway seemed puzzled. "Did I write about that? I must have covered so many stories over the years..." When shown his own article, he read it with apparent interest but claimed to remember very little of his research. "I suppose I must have been quite taken with it at the time. Funny how some stories just... slip away."

His personal notes from the investigation, which he claimed to have kept in a filing cabinet in his garage, could not be located. "I'm certain they're somewhere," he told researchers. "But I've been through that cabinet twice now. Very strange."

Several other researchers have reported similar difficulties. Dr. Margaret Sutherland noted in a 1985 letter that she found herself "inexplicably unable to concentrate" when attempting to organize her Fixers-related research for publication. "I would sit down to work on the material and find my mind wandering to other projects. It's the oddest thing—I completed my thesis without difficulty, but every subsequent attempt to revisit the material has been... frustrating."

A graduate student who attempted to follow up on Dr. Sutherland's work in 2003 reported that several of the archival documents she had cited seemed to have been misfiled or lost. "The librarians at the State Library were apologetic but baffled. Items that should have been in the collection simply weren't there. Or they were there, but not quite as Dr. Sutherland had described them."

Whether these difficulties represent bureaucratic mishaps, the normal degradation of memory over time, or something more unusual remains a matter of speculation.

Galloway's article did inspire some researchers to examine Pioneer's Light and its history more closely. What they found was interesting, if not conclusive:

The house had been associated with occult interests in the late 1930s. A tenant during this period had assembled some kind of collection at the property. Local oral histories describe him as eccentric and reclusive. He departed abruptly in early 1940, and family correspondence suggests there was "unpleasantness," though specifics were never recorded.

The Wentworth family continues to maintain ownership of Pioneer's Light. The house is now part of a larger working property and is not open to the public. Requests by researchers to examine the property have been politely declined.

Theories and Speculation

Over the years, various theories have emerged about R.D. Rowland and the Fixers series:

The Testimony Theory: That R.D. Rowland was someone connected to the Marsh family (perhaps a parent, relative, or family friend) who witnessed or learned of what happened to Constance and Christian in December 1939. The first nine books established the characters and built an audience, ensuring people would pay attention when the final book appeared. The "unsuitable" ending was not a miscalculation but intentional—a way to tell a truth that couldn't be told directly. Critics note that if this were true, the manuscript would have had to be written before the events it describes, unless one accepts less conventional explanations for its origin.

The Warning Theory: That R.D. Rowland was attempting to warn readers about something real, perhaps the dangers of meddling with occult materials, or the way powerful families can cover up tragedies, or the darkness lurking beneath Australia's colonial aristocratic pretensions. The popular Fixers series was merely the vehicle for delivering this warning to a wide audience.

The Composite Theory: That R.D. Rowland combined elements from multiple real events. Including the actual Marsh children, the real Pioneer's Light and its eccentric tenant, local rumours about the Wentworth family, and his or her own experiences or anxieties.

The Coincidence Theory: That R.D. Rowland was simply an author who did thorough research, chose the name "Wentworth" because it sounded appropriately Australian and colonial, happened to set the story in a region similar to Bourke, and created characters whose names and ages happened to match real people. The parallels, according to this theory, are the result of Australia being a relatively small country with limited naming conventions and repeated place names, combined with confirmation bias by researchers looking for connections.

The Literary Subversion Theory: That R.D. Rowland was a sophisticated literary artist deliberately working in the genre of children's adventure fiction in order to subvert it from within. The first nine books were conventional by design, establishing reader trust and expectations, so that the tenth book could violate those expectations and force readers (and their parents) to confront uncomfortable truths about the world: that evil exists, that children are not always safe, that authority figures cannot always protect them, and that happy endings are not guaranteed. The scandal was the point. Professor Hartley's cipher theory fits within this framework: perhaps R.D. Rowland deliberately created a text so overdetermined with meanings that it becomes a mirror for the reader's own anxieties and assumptions.

The Supernatural Theory: Occasionally proposed but rarely taken seriously, this theory suggests that the manuscripts were genuinely supernatural in origin. Written by the spirits of deceased children, or channelled through a medium, or produced through some other paranormal means. Proponents point to the distinctive handwriting, the mysterious blue envelopes, the author's complete absence from public record, and the prophetic or testimonial quality of the final book. This theory is generally dismissed by serious researchers.

Cultural Influence and Contemporary Significance

Puggle Publishing House is largely forgotten today except by specialists in Australian publishing history and collectors of vintage children's books. The Doherty brothers' original vision of producing educational materials for colonial youth has been entirely superseded by subsequent generations of publishers.

Cracking Larks is remembered, if at all, as a minor predecessor to the more successful Australian children's annuals that emerged in the post-war period. Several of the authors who got their start in Cracking Larks went on to have respectable careers, though none achieved lasting fame.

The Furrow's Fixers series occupies a peculiar position in literary history. They are too successful to be entirely obscure, too scandalous to be respectable, too mysterious to be easily categorised. The first nine books are occasionally reprinted by small speciality publishers catering to nostalgia markets, though these editions rarely sell in significant numbers. They are sometimes studied as examples of pre-war Australian children's literature, notable for their distinctly Australian settings and characters at a time when most children's books were still set in Britain.

"Furrow's Fixers and the Big Old Bush House" has never been officially reprinted, though it has appeared in various unauthorised editions and can be found in digital form on websites dedicated to rare and controversial books. Yet it remains, paradoxically, the most sought-after volume in the series. Collectors, scholars, and curious readers all want to read the book that caused such scandal, that ended a publishing house, that may or may not contain coded testimony about real events. Its status as forbidden or lost knowledge only intensifies its appeal.

The book is sometimes taught in university courses on children's literature, Australian Gothic fiction, or the history of literary censorship, where it serves as a case study in authorial intent, reader expectations, and the boundaries of genre. It has also attracted attention from scholars of Australian colonial history, particularly those interested in the social and cultural legacy of attempts to establish an Australian aristocracy.

Some see R.D. Rowland's choice to name the fictional town "Wentworth" and to place a house called "Whyburn" at the centre of a dark mystery as a deliberate commentary on the relationship between colonial power, land ownership, and secrets buried in Australia's past.

The name "Wentworth" carries significant weight in Australian history. William Charles Wentworth was not only an explorer but a politician and advocate who, paradoxically, fought both for Australian self-governance and for the establishment of a hereditary peerage system. The Wentworth family owned substantial properties across New South Wales, including Pioneer's Light near Bourke. To anyone familiar with this history, R.D. Rowland's decision to invert the names calling the town "Wentworth" and the sinister house "Whyburn" suggests intentionality rather than coincidence.

Was R.D. Rowland making a statement about power and its abuses? About the way colonial families controlled not just land but narratives? About secrets hidden in grand houses on properties owned by Australia's would-be aristocrats?

These questions remain unanswered, but they continue to generate scholarly interest.

The identity of R.D. Rowland remains unknown.

The fate of Constance and Christian Marsh, whether they were real children who died tragically, fictional characters who lived only in an author's imagination, or something in between remains unknown.

Pioneer's Light near Bourke still stands, now part of a larger property compound, its grand Colonial architecture looking increasingly out of place amongst more utilitarian modern buildings. The Wentworth family maintains ownership. Whatever secrets it may contain, if any, remain undisclosed.

And somewhere in New South Wales, perhaps in a cemetery near Bourke, perhaps elsewhere, perhaps nowhere, two graves may or may not mark the resting place of children named Constance and Christian, who may or may not have been the Furrow's Fixers, who may or may not have died in December 1939 after investigating something they should have left alone.

In the end, perhaps that is the most fitting legacy for a series about young detectives who prided themselves on solving mysteries: they became a mystery themselves, one that resists all attempts at resolution. The Furrow's Fixers solved their last case and disappeared into legend, leaving behind only ten books, a handful of clues, and the haunting possibility that some stories are true even when they cannot be proven.

Some doors, once opened, can never be properly closed again.

References and Archives

Primary Sources:

• The archives of Puggle Publishing House Co., including all surviving R.D. Rowland manuscripts, correspondence, and business records, are held by the State Library of South Australia (MS 13491). The original blue envelopes in which manuscripts arrived are preserved separately in climate-controlled storage and are available for viewing by appointment only.

• Herbert Wickham's personal papers, including diaries and correspondence (1905-1951), State Library of South Australia (MS 13492).

• Dorothy Ashton's papers, including correspondence with Dr. Margaret Sutherland and contributions to oral history projects, National Library of Australia (MS 9847).

• Edmund and Charles Doherty business correspondence and company records (1887-1926), State Library of South Australia (MS 13493).

Secondary Sources:

• Sutherland, Margaret (1978). "Pseudonymity and Authorship in Australian Children's Literature." PhD thesis, University of Melbourne. Available through University of Melbourne library system.

• Galloway, Peter (1976). "The Real Big Old Bush House?" The Australian, 23 October 1976. Available through National Library of Australia newspaper archives (Trove).

• Hartley, Edmund (1939). "The Cipher in the Nursery: R.D. Rowland's Rorschach Test for a Nation." The Adelaide Review, April 1939. Reprinted in various anthologies of Australian literary criticism.

• "Crackers and Corkers: Publishing Memories from the Puggle Years" (1967). Oral history project featuring interviews with Herbert Wickham, Dorothy Ashton, and former staff members. National Library of Australia Oral History Collection.

• "What Has Happened to Australian Children's Literature?" Editorial, The Sydney Morning Herald, 8 January 1940.

• Various articles on the Fixers scandal, The Advertiser, December 1939-February 1940.

Related Holdings:

• Property records relating to "Ploughman's Furrow" and Marsh family holdings, New South Wales Land Registry Services.

• Wentworth family papers (partial collection, MS 7293), Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales.

• Bourke Shire Council records, including cemetery records (partial, post-1952 fire), Bourke Local Studies Centre.

• Pioneer's Light property records and correspondence, held privately by current owners; access restricted.

• Peter Galloway research notes and interview transcripts (presumed lost following his death in 1981).

Collections Containing Puggle Publishing Books:

• Complete run of Cracking Larks annual anthologies (1928-1940), State Library of South Australia.

• Furrow's Fixers series, first editions (1935-1939), National Library of Australia and various state libraries.

• Various Puggle Publishing House catalogues and promotional materials, State Library of South Australia.

The author of this article acknowledges that certain details regarding the Marsh family and the circumstances of 1939 remain unverified and should be treated as speculative pending further research. Researchers are encouraged to examine primary source materials and draw their own conclusions.